I’m not expecting anything when a box arrives at the Seattle Program Center Bookstore - no return address, no explanation. Inside are old editions of the Mountaineer annuals, the covers softened and yellowed by time. These volumes once marked the rhythm of each year in the club, part record, part reflection. Among the box of annuals is the 1975 edition. I don’t reach for it with any particular intent, but once it’s in my hands, I linger.

What were The Mountaineers writing about 50 years ago? What did they fight for, climb toward, pay attention to? The answer, it turns out, is everything that still matters.

Reading the past, looking toward the future

Between the annual’s covers lie more than a year’s record, a topographic map of a time. No algorithm, no filters, no hashtags – just typewritten dispatches, stark black-and-white photographs, and hand-drawn illustrations.

At the time of publishing the 1975 annual, The Mountaineers stood at the edge of our 70th anniversary. In his essay “Whither The Mountaineers,” then-president Sam Fry reflects on the shape the organization had taken and imagines its path forward. Membership was growing. Trips adopted size limits to reduce environmental harm. Publishing became a growing force, with 30 books already in print. “Where will we be five years from now? Ten years from now?” he asks. His words are rooted in the hard-earned hope of someone who’s seen what fellowship can do. “There is no obstacle,” he writes, “so long as The Mountaineer spirit of goodwill prevails.” It’s a sentiment that could have been written today.

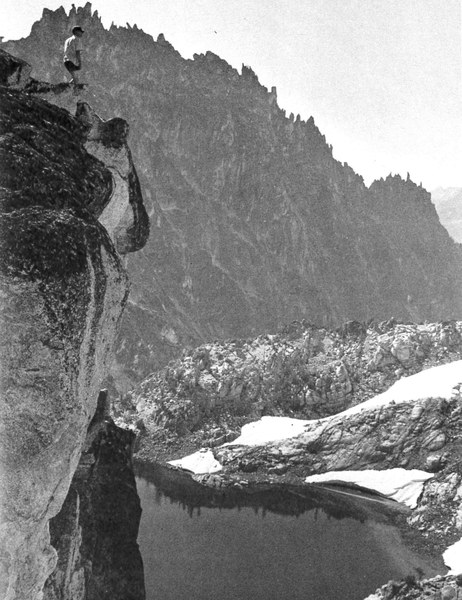

John Warth in the Enchantments, on hip-top overlooking Crystal Lake. Photo by Lou Berkley.

John Warth in the Enchantments, on hip-top overlooking Crystal Lake. Photo by Lou Berkley.

At first, it’s easy to see these pages as a relic. But spend time with them, and the voices come alive: scrappy, sincere, and deeply rooted in the landscapes they moved through and the community they shaped.

The voices in the annual range from the visionary to the irreverent. In “The Great Big Rainier Jamboree,” Harvey Manning recounts the 1951 “mass summit” of Mount Rainier, in which all 81 climbers reached the top (a remarkable feat considering only 200 people summited the mountain that entire year). Manning, as ever, writes with a twinkle in his eye and boots firmly in the dirt. He recalls climbers stuffing socks into their hats as makeshift head protection on the recently reopened Gibraltar route, which he describes as “a head-smasher.” Co-leader Jim Henry, a logger by trade, showed up in an actual hardhat - “the first hardhat any of us had ever seen on a mountain” - an early nod to modern climbing safety.

The story is chaotic, human, and brimming with moments of unpredictable joy, like butterflies a-flutter on the summit. In the final paragraph, Manning reflects on how rare that kind of day had become, even by the 1970s. With summit numbers rising and crowding on the mountain more common, he takes a look at the improbability of it all: three coordinated parties, perfect weather, and a successful summit. “Eat your hearts out, youngsters,” he concludes, aiming his grin at a new generation. A line that, even 50 years later, lands with the same mischievous glint.

Spirit Lake and Mount St. Helens. Photo by Bob and Ira Spring.

Spirit Lake and Mount St. Helens. Photo by Bob and Ira Spring.

A legacy of courage, innovation, & conservation

A brief account from the Administration section mentions the 1975 Annual Banquet, where Jim Whittaker and Dianne Roberts shared the story of their expedition to K2. The story behind their appearance is much more compelling than this passing mention - the team set out to make the first American ascent via the remote and untried Northwest Ridge but was turned back by storms at 22,000 feet. Still, history was made: Roberts became the first North American woman to reach 8,000 meters without supplemental oxygen, a groundbreaking accomplishment in high-altitude mountaineering. The team would return in 1978 to reach the summit.

I turn to page 20 and find an interview with Ome Daiber. “Resting? Baloney!” he says, “I don’t get any relaxation from not doing anything!” Daiber spent over five decades shaping how we explore and safeguard mountain terrain. A Mountaineer since 1931, he made the first ascent of Liberty Ridge on Rainier, co-founded the Mountain Rescue Council, and helped bring organized mountain rescue to the United States. He developed Sno-Seal, created the penguin-style sleeping bag, and joined Bradford Washburn’s 1935 expedition to map the Yukon, an effort later featured in National Geographic. He even met his wife, Matie, on a Mountaineers summer outing.

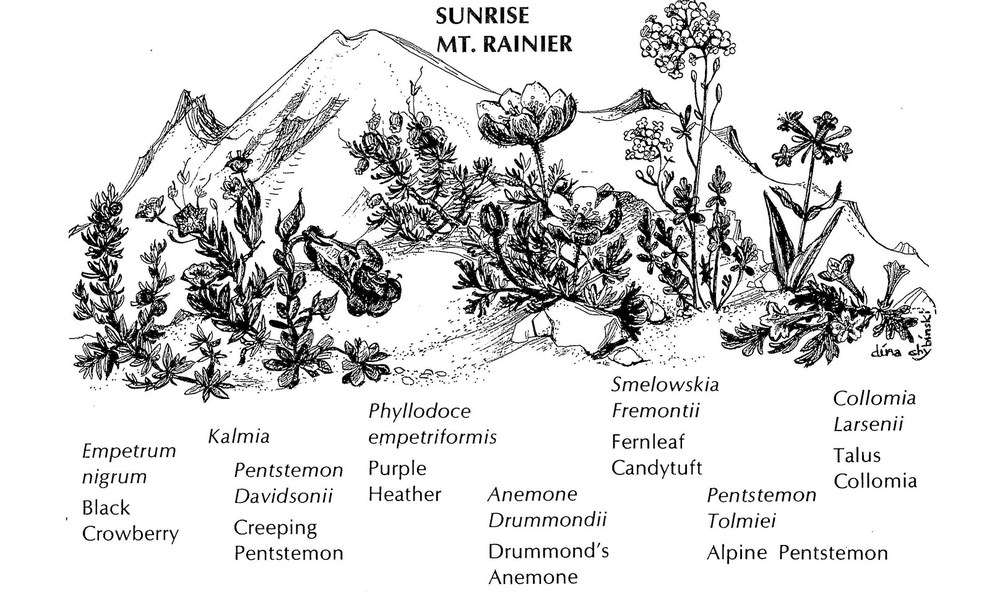

As I read, unexpected corners of curiosity surface: a hoary marmot field study near Mt. Cashmere, a botanical survey on the slopes of Mt. St. Helens (described five years before its eruption as a “perfect, symmetrical cone”), a geology field camp near Mt. Shuksan while Mt. Baker stirred to life. There’s an expedition to the Garhwal Himalaya, a trip to Latin America, and a meditation on the brevity of alpine flower seasons accompanied by delicately inked illustrations.

As always, woven through each Mountaineers story is a strong conservation ethic. At the time, much of the organization’s advocacy centered on what is now known as the Alpine Lakes Wilderness. In 1975, The Mountaineers presented our recently published book, The Alpine Lakes, to Congress. The following year, the Alpine Lakes Area Management Act was signed into law by President Gerald Ford, which designated 393,360 acres of instant and intended Wilderness. This was one of the most hard-fought and significant conservation victories in Washington history.

A Quinault valley fern. Illustration by B.J. Packard.

A Quinault valley fern. Illustration by B.J. Packard.

Who we were, and still are

This patchwork of stories, essays, trip reports, and illustrations is more than archival – not a museum piece, but a mirror. As you read through these pages, you begin to recognize yourself. Maybe your clothes are more tech and your gear is safer… but the GORP in your pocket? Probably the same. And your devotion? That hasn’t changed at all.

We still stand quietly beneath the same peaks.

We still fight to protect the same places that move us.

And that’s why we return to these pages now, 50 years later. Because the past, in this case, is not past at all – it’s part of the living root system from which we draw. These stories are trail markers, annotations on a map, notes scribbled in the margins of our guidebooks. They remind us that to love the outdoors is not just to walk through it, but to be in conversation with those who came before and those who will come after.

We don’t need to replicate 1975. But we’d do well to remember it.

Tender green of lichen / Beside the brown of old -

White granite rocks in meadows / Mid flowers of red and gold.

- Bob Dunn, excerpt from “Splendor,” page 39, Mountaineer Annual 1975

This article originally appeared in our fall 2025 issue of Mountaineer magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, visit our magazine archive.

Add a comment

Log in to add comments.This is lovely--and so lovingly written. Thank you, Katy! “There is no obstacle,” he writes, “so long as The Mountaineer spirit of goodwill prevails.”

Thank you Danielle!

Jim Henrys hard hat was most likely the inspiration for Lloyd Anderson adding Hardhats to the 1951. REI catalog. See page 73 and 74. Book REI fifty years of climbing together. Written by Harvey Manning in 1988. Erin Roach

Katy Clark

Katy Clark