While traveling solo to remote and wild places, I had been in some dicey situations. The risks were real, but I knew of no one else interested in exploring the nether regions of wilderness, nor the Himalayan front range from east to west, nor the ancient trade routes that connect Tibet to India through massive ranges, passes that cut deep, from north to south where borders often go unmarked – and so I had gone alone.

Almost six feet tall, with hair that typically looked like a yellow hayfield post-windstorm, no - I would never blend in with the people of the Himalaya, which might have allowed me safer passage.

I was in Seattle, and making plans again, enthused about another return to the collar of the Indian Subcontinent; it was here I met Fred. He was in his early eighties, also alone, and stalling when our paths crossed. He looked road-weary from outrunning time; it seemed he needed a jump-start and a push, and this I could provide. Fred quickly jumped on board, sharing his maps, giving advice – and jokingly offered to carry my bags as he highjacked my trip.

He was eager to explore, and vibrated with restless energy and a brilliant mind. He had made multiple trips to the Himalaya and was also anxious to return.

We were immediately joined at the hip, and then the heart; friendships are sometimes sudden - just like that! Our heads were conjoined, and our brains synced.

Fred was thirty-five years my senior, and I was a mid-life forty-something. Neither of us was ever alone again.

We made a great team.

We became inseparable and laughed and wisecracked constantly. Fred was the master of side-splitting one-liners and kept me grinning from ear-to-ear, the sort of smile that went on for so long that my face hurt. We shared jokes and wordplay, and everything from meals to secrets to books and warm clothes. But the greatest thing we shared was that we each loved mountains.

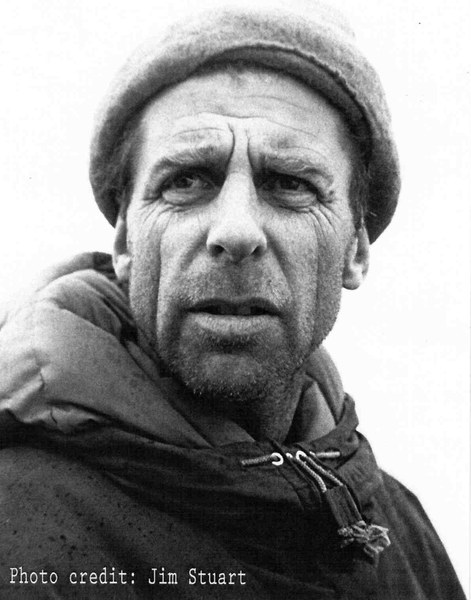

Fred was Fred Beckey, the most famous mountaineer and explorer most people have never heard of. He gave everything to the alpine world, and in return, the alpine world gave him breath and life.

Through a lifetime of dedication and commitment to his passion, Fred had studied and climbed mountains the world over, creating new routes, and ascending rock walls and monoliths that challenge his followers to this day. He shared his findings and routes generously with other climbers, authoring intensively researched guidebooks and contributing to journals and magazines to do so. He inspired climbers to achieve earthly summits and unworldly renewal.

I loved exploring the high, natural world too, but my needs were simpler and not so bold. I aimed for regions where other people seldom traveled: remote, wild and unseen, and craved putting distance between myself and the artificial world. I wanted to see changes in topography, to walk the terrain and through the seasons, to silently observe wildlife and watch birds.

We both took a great interest in other cultures; there was so much to learn.

With his short list of bare essentials and a vast mental repository of what could be procured elsewhere, he could leave at a moment's notice. Anything he considered superfluous, like a toothbrush, was not worth taking. He would have been fine with just a knife and a blanket.

His gray shaggy hair, hunched frame and visible antiquity brought immediate respect to our unexpected twosome. No one would maltreat an elder on remote mountain treks, in latitudes where age earned reverence, and particularly not in nations where ancestors were worshiped. Luckily, proximity to this respect trickled over to me. Those margins where a lone woman might find herself in jeopardy gave way to less peril and I was now out of harm’s way. In this way, Fred’s presence protected me on our far-flung travels and in return I kept him going.

A group photo with the horse handlers who led Fred and Megan to basecamp of Mt. Po’nyu, Tibet, 2013. Photo by Megan Bond.

Slowing down

As our years together increased, age permeated his skin and slowed his heart, but he battled on. His chest wheezed and a cataract made an ill-timed performance, blurring his vision but not his outlook. Arthritis molded his spine into a permanent arch, creating a stooped posture, and he appeared to be carrying a heavy rucksack, with his face and shoulders bowed into a fierce wind, even with no load and no breeze. The effect was fitting for a man who had spent his life doing exactly that, but the pain was a terrible load for him to carry.

Travel to Asia was already compounded by language barriers, and near-deafness added to his struggle. He had taught himself to lip read and observed body language carefully to help him interpret people’s sentences.

Fred had struggled with this hearing loss for twenty years, which by then had become rather acute, but for some reason he could hear my voice, or at least intuit with ease what I communicated. I became the eyes, ears and interpreter on our travels, but he sat in the pilot’s seat as navigator and guide.

Our speed decelerated in those later years. Aches, illness, weakening legs and lungs slowed the pace to a crawl. But still we went, and Fred went on, pained but insisting he was up for any journey – nudging one foot in front of the other. Our bivouacs – spawned by misadventure or necessity – became less frequent, but the sleeping bags were still put to good use as we camped out and star gazed. Our faces crevassed with time, but as we wrinkled, so did we beam.

Fred enjoying the sunshine, Ventura Beach, CA, 2017. Photo by Megan Bond.

Dreaming of the Valley of Flowers

By the spring of 2017, we had spent a full year planning our next trip to the Himalaya, and had pushed our planned journey into 2018 to accommodate uninvited afflictions.

Fred had beat-back death on more than one occasion: sometimes by luck, usually by skill, but more recently by sheer stubbornness.

Regardless, he insisted we were heading to the Garhwal in the Northern India State of Uttarakhand, and the Bhyundar Valley, known as the Valley of Flowers. A journey to this lush, high altitude basin near the Zanskar had been a dream of mine since I was a teen, after I read a book of the same title by the Himalayan explorer Frank Smythe, and Fred was intent on making this dream come true for me. The Valley of Flowers is more accessible than most places we had ventured, which Fred described as pedestrian by comparison. Nevertheless, we anticipate a 2018 spring departure.

Magnifying glass in hand, Fred would spread maps of the Himalaya out on the table and pour himself into them, highlighting various colored spirals that represented elevation gains, topographical features, or mountain roads. He would drink cold coffee as he plotted lines and routes from point A to point B to point C, and I would use my primitive Tibetan language skills to find meaning in various place-names he occasionally asked me about. Sometimes I was even right.

By then, Fred was ninety-four years old, and reluctantly using a wheelchair, pushed by me. As a result, this forthcoming exploration to the Garhwal was incorporating the need for porters to shoulder him in a hoisted sedan chair to access our remote trekking destination. With such accommodation, surely, we could keep going and reconnoiter this isolated mountain valley.

We made further, long-term itineraries for adventures that went years into the future. How could we know that these would be the last few months of his life? But our dreams had been delusions and would not live beyond the fall.

Fred and Megan in a café in Darjeeling, India, 2012. Photo by Beren Moloney.

Saying goodbye

By the time our twelve years together had ended – at his death that October – we had explored thousands of wild miles and treacherous mountain passages. We had traversed overland on foot and by horseback, and hitched rides in impressively deft vehicles, held together by rust, twine, and salvaged wire.

This middle-aged woman and that elder of a man had wasted no time. Together we explored nine countries, scrambled and climbed in eleven U.S. states, crossed countless snowfields, and bushwhacked through jungled vines and branches. Our explorations had taken us worldwide, but there were also trips within North America, including the desert southwest, the Coastal Range of British Columbia, the Sierras, Moab, the Rockies, and hikes and climbs within our beloved Pacific Northwest. We had wriggled under giant, fallen trees that were too high to climb over and too horizontal to go around, pushing and pulling each other and our backpacks underneath toppled timbers to the other side of the blockade.

As companions and the best of friends, we had traipsed through literal hell-and-high-water, enduring lowland floods, mountain storms, and had trucks and buses break down on eroding roads at high-altitudes in Tibet and Nepal. We figured out how to fend for ourselves when logistics failed, and nature overwhelmed us. We had a blast.

We shared nearly every day of every year, either in the wilds or the city, and occasionally by phone if one of us was away, but we remained connected to one another in either world.

Fred spent close to twenty percent of his adult life with me, and by then thirty percent of my own grown-up years were with him; our time together had outlasted most marriages. No wonder I miss him so much.

He felt obliged to make up for the pace of our journeys not being swift and quick, and would mutter the dictum to me as much as for himself: “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go with a friend.”

For most of his life, and well into his middle age, Fred had been a torpedo, outdistancing climbers half his age who struggled to keep up with him. He would sometimes lose patience if these young cragsmen fell too far behind as he gunned up mountains, and they were left humiliated and frazzled in his dust.

Lives intertwined

In the last week of his life, Fred intoned a tender and unwarranted apology. Repentant, he said to me, “I’m sorry I held you back.”

But I insisted that there was no apology necessary.

I would never have traded circling the Earth in long distances with Fred, for racing around the world without him.

I wouldn’t have wanted our journeys any other way.

Fred Beckey on the summit of Grand Teton, 1963. Photo courtesy of the Fred Beckey Archive.

Fred Beckey was a legendary Northwest climber, environmentalist, historian, and Mountaineers Books author. He wrote the original guidebooks for the North Cascades (the Cascade Alpine Guides, published by Mountaineers Books), and is noted as “one of America’s most colorful and eccentric mountaineers." He’s earned unofficial recognition as the all-time world-record holder for the number of first ascents credited to one person. On October 30, 2017, he died in Megan's arms after a brief illness. He was 94 years old. Megan is working on a biography of Fred, to be published by Mountaineers Books.

This article originally appeared in our Spring 2021 issue of Mountaineer Magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, visit our magazine archive.

LEAD IMAGE OF Megan and Fred at icicle canyon after a day at the crags, 2007. PHOTO courtesy of the fred beckey archives.

Add a comment

Log in to add comments.Beautiful tribute - thanks so much for sharing.

Megan, This is a brilliant tribute to friendship, adventure, mountaineering, to two lives well-lived--and to the legendary Fred Beckey. Thank you.

Megan Bond

Megan Bond