Trip Report

Field Trip Mt Rainer - Sunrise

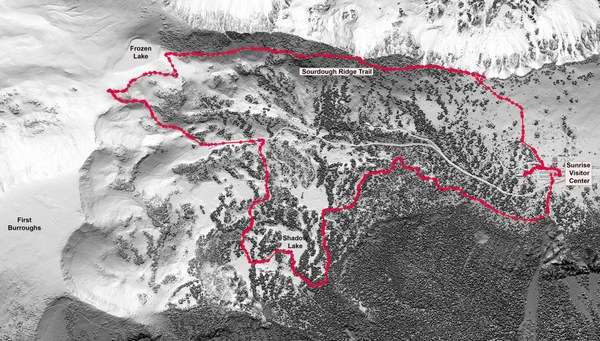

In the fog, we hiked the loop from Sunrise to Frozen Lake, to Shadow Lake and back to Sunrise. The clouds gave an eerie feeling to the landscape.

- Sat, Aug 16, 2025

- Field Trip Mt Rainer - Sunrise

- Mount Fremont Lookout, Berkeley Park & Skyscraper Mountain

- Naturalist

- Successful

-

- Road suitable for all vehicles

-

The trail was wide, well-maintained and easy to follow. Even in the fog, there were a fair number of people along the trail.

The Wonderland Trail below Frozen Lake, looking back north toward the lake. Burroughs Mountain is in the background.

The water rushed down the White River in a torrent.

Rain had fallen for most of the night, lessening to a heavy fog with mist by morning. Before leaving White River Campground to meet my group at Sunrise, I checked the Wonderland Trail Bridge across the White River. The flow had risen substantially during the night. Water rushed down from this side of Mount Rainier and Emmons Glacier. The clanging and banging of rocks could be heard over the general torrent. The water splashed against the bottom of the log bridge, and the approach had water around the rock walkway. The Park Service had placed warnings for backpackers to consider avoiding this bridge and hiking the road between White River Camp and Fryingpan Trail.

Clangs, bangs, and thuds came from the water. Softball, perhaps even basketball, sized rocks slammed against one another. It was an ankle destroyer for sure. The power was incredible, and to think sometimes even bigger flows burst out of the glacier. Melt lakes will form on or under the ice, and when their dams break, a wall of water, a debris flow, would come rushing down, rearranging the channel, taking out the alders and plants that had established in the flood zone.

I looked up toward Yakima Park, a few thousand feet above the river, and there was no sign of it through the white.

The hike to Sourdough Ridge was through thick fog. It gave an eerie feeling to the landscape, a sense of mystery, and what might be around the next bend. Water droplets clung to the subalpine firs, emphasizing their twists and turns. McNeeley Peak, only a short distance north of the crest, wasn’t visible through the milk soup. A small gap in the white allowed details of the andesite to pop out. Below the ridge’s north side, a marshy area suggested where a tarn had been, originally carved by a glacier coming from below us.

The soft light made the greenish flowers on the hellebore almost glow. The inability to see far caused us to pause and look more closely at items beside the trail. The six petals of this lily stood right out while the six stamens appeared almost fused. The white flowers of pearly everlasting had a pastel feel. The rain had mangled the yellow flower of an agoseris, making it look like a horrible hair day.

A golden-mantled ground squirrel scurried across the trail and up onto an overturned stump. It was manipulating something with its front paws while working the item with its incisors. In August, they would be busily collecting and caching items for the long winter. They do hibernate but also wake up periodically to eat a little. The winters would be long here; snow probably comes in October and lasts into late June. That is a long time to be dependent on what one has in their burrow. The grocery store near my house is closing. I often walk to it in the late afternoon after I decide what to make. I’ll need to change my behavior to survive.

The common juniper seemed richer in color than when the sun is bright. It was as if the rain and mist had made each leaf glow with a radiant green. The hillside above the trail took on a fall feel with the knotweed adding pinks and reds to the juniper and darker green of the firs. It made me stop, repeatedly. Something seemed different. I’d hiked this trail dozens of times over the last decade, but only once did I hike part of this trail in fog. These conditions had changed my focus, looking more closely at things. We still moved along at a typical naturalist pace, not too fast but making progress. The plants seemed to be rejoicing with the rain. Might they be storing up water to replenish themselves for winter?

My thoughts, though, were puzzling me. A clump of subalpine firs on a rocky bump below the trail made me stare. The firs had the krummholz shape typical of trees battered by winter conditions. The mass was two, maybe three dozen feet long, a dozen or so wide, forming an oval of low mat-like branches. A few “flags” extend above on the left side. These were twisted and battered, most of the branches stuck to the left, the leeward side, and those on the right were dead. One flag appeared devoid of needles. The “mat” would be buried by winter snows, protected from the whipping wind that might carry ice crystals, while those flags would receive the brunt of winter storms. What might those conditions be like? How long, a few minutes at best, would I survive?

A high-pitched squeak came from the scree behind me. There, on a rock, sat a pika. His rounded ears accented the large eyes and cute face. It leaned forward, raised its nose a little, and out came that high-pitched tone. It was warning all its neighbors that we were in their area. Several pikas scurried across rocks in both directions. Even though it was noon, they were still active. Mammologists say that these relatives of rabbits don’t like heat. In temperatures above eighty degrees, they retire to their dens. Climate change has been creating survival problems for them. In places like Nevada, they have disappeared from many mountain ranges, having been pushed higher and higher on the slopes because of warming temperatures, until there was no longer enough space for a population to survive.

Survival, there was that word again. Remarkable, pikas don’t hibernate. They are related to rabbits and not rodents. All through the winter, they must eat. So, in the short summer, they are busy harvesting vegetation, carrying it to their rocky burrows. I watched one in the North Cascades harvest fern leaves, and it laid them out on a rock to cure in the sun. Pikas move their cured food into a larder in their rocky home. This cool, cloudy day would let them harvest all day long. These guys don’t dig a burrow like a marmot or ground squirrel. They must find a suitable place under rocks, so these scree fields are perfect for them.

One ran across several rocks, disappearing down into a dark crevice. The snow cover is vital in winter, too. A thick layer of snow over these screes provides insulation that helps keep their homes from going extremely cold. Less snow can mean that pikas will freeze during a severe cold snap. The Park Service has a cooperative program happening right now to determine the status of pikas in Mount Rainier National Park. To my eyes, the population still seems to be doing well, but I look forward to hearing their results. Baseline information is essential in understanding change.

On the trail along Frozen Lake, numerous flowers still had blooms. A nice clump of Elmera in a rock ledge made me stop. I never seem to remember this flower. The Elmera grew out of cracks between rocks, making me wonder about soil and conditions. They must be highly resilient to succeed in that manner. Northern goldenrods had vivid yellow blooms, and the alpine lupines had large water droplets on their purple flowers and leaves. The hairs on their leaves help capture moisture for the plant. It is an adaptation for these dry high habitats. The usually white flowers of alpine buckwheat had a slight red tinge. This tinge is probably a result of age. The leaves and flowers of this species lie close to the ground, again as protection from the drying winds. The pumice, ash, and broken rocks that comprise this soil likely hold very little water. These plants need adaptations to protect them from the wind, grab water when they can, and store food in their roots.

The Wonderland Trail connects Frozen Lake with Shadow Lake and drops through a series of dips and bumps. The edge of First Burroughs was barely visible through the fog, and down toward Shadow Lake, the trail disappeared into a sea of white. Without the long views, I studied the topography more than I had on previous hikes. Details and suggestions were popping into my mind. How had this landscape, the path of our trail, been sculptured?

Small glaciers might well have shaped this topography. During the Younger Dryas period, the northern hemisphere cooled to temperatures similar to those of the Pleistocene. Temperatures had risen sharply about 13,000 years ago and then dropped again to a low around 11,000 years ago before rising again around 10,000 years ago. Here, the upper part of the trail went through a cirque in the mountain and then out over a lip. From lower on the trail, looking back up, another cirque suggested that maybe the glacier came over the lip and then was added to by additional snow accumulation.

Down the hill, a lateral moraine made a boundary between where this glacier flowed, and another formed in a cirque along the north side of Burroughs. The other cirque was a rounded bowl along the ridge, where ice had built up and then flowed down, carving a depression on the flats. The trail ran down the one glacier’s scrape, the moraine petering out where the other glacier merged with the first. The combined flowed toward Shadow Lake. Perhaps, these carved the tarn that is now Shadow Lake? We needed a time machine! Of course, all this probably had ice during the cold parts of the Pleistocene. So much to learn. Were these ridges void of life during those cold periods? I stood looking back and forth, a healthy mixed subalpine zone now.

This landscape was sculptured, rough in topography, with a diversity of forms. How does one put this all together in their minds? It was then that the word “lidar” popped into my mind. The Washington Department of Natural Resources had a website that allowed me to look at the topography of the Columbia Plateau in detail, seeing all the ups and downs of the hills. Maybe that would help. When I got back to Seattle, I zoomed in on a close-up of this area of Mount Rainier. I exported the lidar and converted it into a shaded relief map to help understand how glaciers had carved this section of Yakima Park. It showed numerous cirques in the area, all suggesting the ice flowed southeast, eventually coming together to tumble over the sides of Yakima Park and down toward the White River. A small glacier had come down along the trail’s route, but other, larger cirques probably contributed a lot more ice that helped mold this section of the park.

Back along the trail to Shadow Lake, a hoary marmot rose on its hind legs to survey the meadow. My attention immediately jumped from geology to what this large rodent might do. This one looked plump, like it was on its way to being ready for its winter nap. They put on as much weight as they can during the summer, eating voraciously and then hibernate through the winter. Our one ran across the trail and into the next meadow, where it stood again on its hind legs, repeating this movement and gazing several more times. The behavior could be checking for predators, or it might be looking for another marmot. Each time it stood, it seemed to hold the position for a long time. For the next fifteen minutes, it kept up its searching and finally disappeared behind vegetation and rocks. What was on its mind? The breeding season ended in late spring. They do have a social system, so maybe it was trying to find another marmot. They often live in colonies, with a dominant male, one or more females, and young. Perhaps this individual was a male trying to disperse and find a new territory where he could start a new group? Dispersal is a dangerous time for animals. They are often exposed to higher predation rates and won’t have a ready burrow to hide in. Survival again!

The subalpine meadows had a scattering of flowers. Clumps of western pasqueflower had their seed tops looking like old men’s beards, and Cascade asters still had their purple disk and ray flowers, and seeds would be coming. A nice patch of bog gentian grew near Shadow Lake. Water droplets clung to their leaves but appeared to have come off the flowers. The blossoms were all closed, maybe to protect their reproductive parts from the rain. This species blooms late in the summer, after most subalpine plants have finished blooming, but while pollinators are still active. More to learn about the adaptation of this species. Those pollinators are critical for these species to produce seeds and a new generation.

The rain left little beads on the subalpine firs and whitebark pines. The new growth on the fir was a gray-green, while the previous year’s growth was a darker green. I’d not noticed that so well before. The five-needle clumps on the whitebark pine were tight, not loose like on western white pine. A fir had its grayish cones on some low branches, allowing us to study them. I should come back with a telephoto lens and look for cones on whitebark pines. Their cones tend to be high on the tree, and trees don’t produce cones until they are fifty years old. Maybe in September, I can find a place with trees down a hill so the cones might be at eye level, and maybe Clark’s nutcrackers will be working them.

The meadows below Sunrise still had fog at 3 PM. The conifers had a blurry texture from the water vapor. It made the hiking mystical as if we were in a prehistoric wonderland. I willed an elk, deer, or bear to walk by, but no luck. The rain should help many of these flowers set a good seed crop. The first snows might only be weeks away. Winter will be here soon.

Thomas Bancroft

Thomas Bancroft