Trip Report

Field Trip Mt Rainer - First & Second Burroughs Mountain

Hiking to First and Second Burroughs gave our group a chance to explore time, geology and this National Park. The day was beautiful with clouds moving across the mountain. A few flowers still bloomed and the geology had lots to show.

- Thu, Aug 14, 2025

- Field Trip Mt Rainer - First & Second Burroughs Mountain

- Burroughs Mountain

- Naturalist

- Successful

-

- Road suitable for all vehicles

-

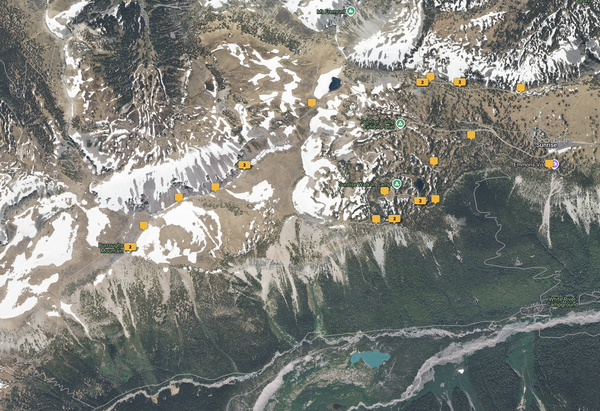

Our hike to Second Burroughs. The flags are locations of photographs used in this report. Note: this satlitte map is from Adobe Lightroom and does not reflect the condition on the ground that day we hiked. The trail to Second Burroughs is wide and easily hiked. Some rocks in places, but with care, it isn't an issue.

Cascade Asters continue to bloom in mid-August. This section of the trail near Shadow Lake had many flowers.

Cascade Asters continue to bloom in mid-August. This section of the trail near Shadow Lake had many flowers.

Scattered clouds overhung Sourdough Ridge and Mount Rainier. It was a beautiful August morning; a light breeze gave a tang to the air, and the view in all directions was of mountains. The haze to the north blocked us from seeing Mount Baker or Glacier Peak, but everything closer was visible. Cascade asters still bloomed in the meadows. Several Clark’s nutcrackers had given their squawks as they darted from tree to tree. Perhaps, they had started harvesting whitebark pine seeds. Some pines had cones near their tops.

“There, is that one?” someone said. Sure enough, a black-and-white bird, bigger than a jay and smaller than a crow, flew across the trail to land on the top of a tree. This bird and whitebark pines have evolved a mutualist relationship. The pine produces a larger seed than most pines; the seed lacks a wing, and the cone doesn’t open. The nutcracker splits open the cones with its pointed chisel-like bill and harvests the seeds. The bird has a pouch, like a built-in grocery bag, under its tongue. They can fit 15 to 20 whitebark pine seeds in it at once, and then they carry them to a cache. Each nutcracker may make hundreds of caching trips, and the flock will cache tens of thousands of seeds. The birds put each pouch-full of seeds in a separate hole and return to collect seeds even in the following spring when they are feeding young. They remember! Both benefit: the bird has a nutritious food source, and the tree has its seeds dispersed and planted in good germination sites. The birds don’t manage to recover all the seeds.

“Let’s head east a short way,” I said. Other trees typical of the subalpine zone grew in clumps. An impressive thicket of Alaska yellow cedar had its branches sticking out. Their flat leaves tend to hang down as if drooping, whereas the lower-elevation red cedar hold them more level. Subalpine firs with their bottle-brush needles grew in clumps. When one becomes established, it helps change the microclimate around its base, making it ideal for other trees to germinate and grow. Looking across the meadow back toward Sunrise parking lot showed how trees are gradually taking over the meadow.

The rock underlying our trail is andesite that originated from Mount Rainier. It flowed as one of the first significant eruptions of the newly forming volcano. James Vallance and Thomas Sission of USGS date it at 504,000 years ago. The lava apparently flowed between thick Pleistocene glaciers that filled the White River Valley and the valleys to the north. It seemed all too hard to believe. I’d brought everyone eighty yards east before heading toward Burroughs to show them the results of a later eruption.

Along the north side of the ridge lies a layer of yellowish-white pumice and ash. It is more than six feet thick, partway over the edge, and evident for several hundred yards along the slope. Vallance and Sission said this is biotite rhyodacite. Apparently, its composition is partway between dacite and rhyolite in silica and other minerals. Rapid cooling of lava rich in silica will form rhyodacites. The geologist said this came in a Plinian fall, which I interpreted as a catastrophic eruption like what happened with Mount Vesuvius that buried Pompei in a layer of ash. Plinian eruptions release large amounts of ash, gas, and pumice, forming a distinctive mushroom cloud. I stood in amazement, thinking about what this eruption must have been like. The cloud of material probably shot thousands of feet into the atmosphere. I just learned of this layer in the previous month and wondered how many times I’d hiked here, oblivious to what happened. The geologists go on to say that this appears to be the only Mount Rainier eruption known to have phenocrystic biotite, which is large crystal biotite. I’m not sure if that means this eruption was the only one with massive amounts of ash? The eruption apparently happened about 200,000 years ago. After a pause to absorb these ideas, we head west along the ridge.

The books say that sourdough ridge is composed of andesite. Andesite has a little less silica and quartz than rhyolite and more than basalt. It is a continuum, though, and related to how the molten rock left the volcano. Rhyolite, the highest end of the silica composition, tends not to flow well and often is ejected in explosive eruptions. A rock along the trail that appeared to have had a piece cracked off during the winter shows the fresh, delicate texture of the andesite. Crystals tend to be small because the lava cools quickly.

The showy Jacob’s ladder was past flowering, but the Cascade asters had lots of blooms. It took some careful watching to find scarlet and magenta paintbrushes in bloom where they were close enough to the trail to see their leaves. Scarlet has a sword-like leaf, while the magenta has a three-pronged fork-like leaf. Stewart spotted some Rainiera stricta still in bloom. This plant has a restricted range and is always good to spot. Most of the penstemons had developed seeds, but some of the small-flowered penstemons still showed enough of their bloom to be recognizable. At the beginning of our trip, I’d told everyone to ask questions about plants even if they had asked about the same one earlier. On my first trip along this trail, I asked the leader to identify Sitka valerian a hundred times. Everyone laughed and then wanted to see one in bloom, but all we could find were leaves.

As we passed along one of the rock cliffs, I looked back to count the group and noticed patterns in the rocks I’d not seen before. A four-foot-by-four-foot chunk of flat rock was positioned right against the trail. “Look at this,” I said, running my hand over the surface and feeling the texture. The rock was rough and bumpy, but it didn’t catch on my fingertips. I took a couple of steps backward to let others see and waited for Richard and Stewart to come forward. I suspected breccia, a rock formation I’d only read about and seen on one of Nick Zentner’s videos. I’d tried to make a rock in the North Cascades into breccia the previous week, but neither Richard nor Stewart had agreed. Could this final be some?

Geologists define breccia as angular rock chunks, sometimes large, cemented together in a matrix of finer-grained igneous rocks. It can happen underground or during an explosive volcanic eruption. Darker rocks, some in complex shapes, seem cemented into a gray matrix. It might be that some lava had already hardened and then was picked up, rolled along by magma flowing along this ridge. Or maybe it is formed by a combination of pyroclastic flow, tearing rocks out, and then combining it with magma.

Stewart and Richard stepped forward, took a quick look, and both simultaneously said “breccia.” They explained the process of how this might have formed. I stepped backward a few more paces to ponder all that is here, looking back at Mount Rainier, towering up through the drifting clouds. My GPS said it was over seven miles from this point to the summit. Had some of these fragments been blown out of the crater to be incorporated into the lava here? Three or four parties passed us, maybe a dozen people, while my friends were explaining. How many wondered about these rocks? Once, a friend and I stood here for several hours to photograph the stars, and we never noticed the breccia. Heck, I didn’t even know the word until this summer. This planet is remarkable.

Most of the flowers in the alpine zone had moved into their seed phase. The pale agoseris had white, fluffy seeds, much like a dandelion. Stewart pointed them out, telling how the wind can catch the umbrella-like white filaments and carry the seed to a new site. The shrubby cinquefoil had a few yellow flowers, and some of the alpine lupine still had its lavender blooms. I couldn’t get anyone to kneel to smell the alpine buckwheat. I made the mistake of telling them that they smelled like boot socks that had been worn for five days straight.

“Krummholz,” Lynn said, pointing at a clump of subalpine firs and whitebark pines. “The word is German and means crooked wood,” she continued. Above about three feet, the trunks rose with few branches that primarily pointed southeast, away from prevailing winds. The bottom parts of the trees looked like thick mats, with lots of horizontal branches intertwined, more like dense bushes. Some of those branches will root themselves, helping add to the laying and their resistence. This growth form is a result of the harsh winter conditions found on these ridges. The wind blows snow and ice crystals. The parts of the tree above the snowbank are battered, killing buds on the windward side, twisting growth patterns. The parts protected by snow respond by growing sideways, forming the thick mat.

“Look at this hillside above the trail we just hiked,” I said while pointing toward Sourdough Ridge above and a little east of Frozen Lake. The talus slope had clumps of mostly subalpine firs spread between rocky scree. Each clump showed the characteristics of Krummholz. I could imagine the snowpack along the hill and the wind whipping across the snow, carrying ice crystals that battered any trunk sticking above.

First Burroughs

A golden-mantled ground squirrel sees if it can get some food from us.

A golden-mantled ground squirrel sees if it can get some food from us.

After a snack break by the junction with the Wonderland Trail, trying to fight off golden-mantled ground squirrels, we headed to Burroughs. The trail wound up the north side. The scree went up and down from the narrow trail. Rocky Mountain Goldenrod still had a few yellow flowers. A Smelowskia still in bloom was a good find. I’d seen cliff paintbrush along this section in July, but no sign of any in flower in mid-August. Lynn discovered a haircap moss, Polytrichum species, amongst some rock rubble on the upside of the trail. I think of this genus as being in the dense lowland coniferous forests, so finding it up here just shows the adaptation abilities of Bryophytes.

On top of First Burroughs, a wide spot on the trail gave us a place to rest and pull out a sandwich. Mount Rainier rose to the west, draped in moving clouds. I set my camera up to do a time-lapse of the clouds while we ate. Twenty minutes would be condensed into a less than a minute video. The panorama to the west and north was spectacular, so much geologic history right here. Geologically speaking, the rocks upon which we sat were relatively young; the Burroughs-Sourdough Ridge lava flow occurred a little over 500,000 years ago. I’d always thought that most of the mountains immediately north of here were of similar age. No, Mount Freemont, Skyscraper Mountain, and Sluiskin Mountain are all much older, part of the first phase of Cascade building, older than 20 million years ago. Stewart noted, "Mount Rainier is just a baby when one realizes that the Cascades have been building for 46 million years."

The ridge to the left of Skyscraper Mountain had a large subalpine meadow below its crest. The Wonderland Trail crossed the meadow and then up over a pass at the right end. But the ridge was what I was trying to study. According to Vallance and Sisson, this ridge is bedded breccia overlain by andesites of the Burroughs Mountain flow—the breccia formed by pyroclastic debris that has hardened and fused. The authors said the structure shows that these two events (pyroclastic and lava) happened in rapid order. It made sense that this volcano had pyroclastic flows associated with its eruptions, but I’d not thought about that before.

Grand Park is just to the right of Berkeley Park’s valley and behind part of the Fremont. Its flatness is the result of an andesite lava flow happening about 445,000 years ago. Apparently, it is the longest flow from Rainier’s summit, going 13.5 miles from the top. What I found so astonishing is that the flow is now cut off from its source. Probably, subsequent Pleistocene glaciers cut through the Berkeley Park valley and severed the line. The geologists said that it looked like the Grand Park flow, like the Burroughs-Sourdough flow, went between ice. I speculated to Richard and the others that perhaps the lava had flowed across the ice in this valley.

I handed around copies of Figure 39 from Vallance and Sisson. They labeled the debris we could see below the talus slopes of Burroughs as McNeely Drift, possibly from the Younger Dryas period. So much wrapped up in those few words, all of which were new for me on this trip. The McNeeley Drifts are glacial moraines created between 9,500 and 11,300 years ago during a period of extreme cooling after the end of the continental glaciation. Temperatures in North America went up to something like now between 13,000 and 12,000 years ago and then plummeted back down to levels similar to the Pleistocene for a few thousand years. Then they rapidly rose again around 9,000 years ago. Some geologists think this cold spell was a result of massive amounts of fresh, cold water flowing into the North Atlantic that temporarily disrupted the Atlantic circulation. Glaciers would have grown and formed, especially on north-facing slopes like this. Here, we could see the undulating topography that showed how the ice had moved rocks around. Off to the right, the stair-step benches emerging from Berkeley Park and extending back toward Frozen Lake are composed of rocks from both the Burroughs Lava flow and the older Fremont rocks, all of which were mixed by glaciers.

Second Burroughs

“How are folks feeling?” I ask as we put our packs back on our shoulders. “I’d like to go to Second Burroughs if everyone is up to it. It is less than a mile from here.”

The Southwest corner of Second Burroughs (elevation 7,388 feet) provided a fantastic look at Mount Rainier (14,410 feet). The volcano seemed to rise almost straight up, more than a mile higher than our perch. On the right, Willis Wall rose above Winthrop Glacier, then, moving to the left, was the summit with Steamboat Prowl below it, then across Emmons Glacier to Little Tahoma peak, which was covered by a billowing cloud. So much history, so much geology, right here, beckoning for an explanation.

Several in our group found a comfortable andesite slab to sit; others stood on the broken chunks. Richard moved beside a Krummhotz subalpine fir. He’d brought some graphics for us and began to explain some of Rainier’s history. Fifty-six hundred years ago, the volcano was higher than it is now; how high is controversial, some geologists think only a little, others as much as a thousand or two thousand feet higher. Then, suddenly, possibly in response to an earthquake, this entire side of the mountain slid away. An incredible cubic kilometer of rocks, ice, water, and mud slipped down the two forks of the White River. This event is known as the Osceola Mud Slide, and it is the largest lahar in recent times. A slurry of cement-like material, maybe as much as five to six hundred feet high at the White River Campground and traveling between fifty and a hundred miles per hour, tore through the valleys. The flow went as far as Puget Sound, reaching Tahoma and the outskirts of where Seattle now sits. The town of Eumnaclaw is built on nineteen feet of Mountain Rainier rubble. Richard pointed across to Goat Island Mountain, “The splash went 1500 feet up the mountain to the area of Baker Point.” It took a while for this to sink into our brains. We tend to look at these mountains as permanent, but they are a work in progress.

Stewart extended his hand toward Willis Wall, “See the layers, it is lava, ash, lava, and the rocks are weakened by the heat of the mountain and by acidic water. These volcanoes are a pile of rubble and they erode away quickly once they stop growing.”

Vallance and Sisson’s Figure 40 showed that a piece of an ancestral Mount Rainier (~ 1 million years ago) is still at the base of Steamboat Prowl. And Goat Island Mountain is much older, with rocks solidified back in the Tertiary, in the first phase of Cascade building. I thought, “What a classroom,” as I looked at everyone paying attention to Richard and Stewart. This learning is the Mountaineers!

Hike Back

We gathered our packs and began retracing our steps, hanging a right to take the south side of First Burroughs, where our view onto the White River and Emmons Glacier was grand. On the trail down, I began to think about time. I first hiked to Second Burroughs in 2014. At that point, I was just learning the flowers and knew nothing about the geologic history. With Mountaineer friends, we are now exploring and learning about the details of 40 million years of Cascade building. I had to pinch myself when I realized that for one-sixth of my life, this area has stimulated fascination.

I glanced down at White River, where there was the kettle lake formed during the Little Ice Age, the lateral and terminal moraines also created during that period, and Goat Island Mountain, a much older formation of rocks. How to comprehend time?

The cones of Englemann spruce and subalpine fir brought me out of my mind. They were at eye level, giving us a chance to study the differences.

On a rock cliff, clumps of lace lip fern, Cheilanthes gracillima, grew in abundance. Their delicate leaves added some softness to the day. The clouds over Rainier had thickened, and the summit was no longer visible.

The subalpine lupines near Shadow Lake had thousands of seed pods. In July, this patch was in full bloom.

Now, however, many bog gentians, Gentiana calycosa, were in flower. Stewart added, these gentians always give me a feeling that fall is just around the bend. Edith Shiffert in her poem "Quest" mentions these flowers as a metaphor for life.

Their purple flowers point straight up as if beckoning for a gift or maybe offering their knowledge. A purple wine-goblet of wonder!

Thomas Bancroft

Thomas Bancroft