Trip Report

Field Trip Mt Rainer - Eastside Trail

The Eastside Trail runs along Deer Creek, Chinook Creek, and the Ohanapecosh River in eastern Mountain Rainier National Park. We did it as a through hike from the Deer Creek Trailhead to the Stevens Canyon Entrance.

- Wed, Aug 13, 2025

- Field Trip Mt Rainer - Eastside Trail

- Eastside Trail (Mount Rainier)

- Naturalist

- Successful

-

- Road suitable for all vehicles

-

The trail was broad and easy to hike, with plenty of room for folks to congregate around something to examine.

This bridge needed some repairs but was still crossable with care. One bridge needed repairs, having fallen in the middle. We were able to cross it without any problems, taking it one at a time and being careful not to step on the one loose log.

The air seemed cool for a mid-August morning. The tall trees and thick understory provided natural air-conditioning, and the sounds of the creek below us made the place sublime. Some of the Douglas firs must have approached 6 feet in diameter. The western hemlocks and Pacific silver firs were massive, as well. All towering one hundred feet into the air, their thick canopies providing a soft overlay. Ferns, mosses, and herbaceous plants covered the forest floor in luxurious growth. There are so many things to study, identify, and marvel about. I'd begun worrying. My Mountaineers' group had been on this trail for almost two hours, and we hadn't made one mile! It was seven miles to the parking lot where we'd left our cars to shuttle back to the Deer Creek Trailhead.

Deer Creek flows down from the mountains south of the Naches Peak area and meets Chinook Creek and then the Ohanapecosh River in eastern Mount Rainier National Park. The Eastside Trail parallels these waterways and SR 123. It starts at Cayuse Pass, but we caught it part way down. The forest here is the mid-elevation coniferous type typical of the Cascades. Only enormous Douglas firs were present, no young ones, indicating that a disturbance that gave them a chance to establish occurred about a thousand years ago. They are shade intolerant, and gradually the western hemlocks and Pacific silver firs replace and dominate this old-growth forest. Both those species readily grow in the shade, waiting their chance to shoot into the canopy. This hike would feature different species than the ones found in the subalpine and alpine meadows that I typically visit at this time of year.

As the trail dropped down toward the valley floor, a tumbling cascade sounded to our right. Water fell over a series of ledges, creating a fantastic view. The cliffs on one side had ferns clinging to the rocks, creating a wonderful garden. Most were maidenhairs, but others were intermixed. In the soft light, the scene, sounds, and smell of water created a magical atmosphere. Lung lichens grew on trunks and hung from low-down branches. Around Seattle, we discover these mainly after a wind has knocked them out of the canopy. It was fun to see them growing attached. These are epiphytes, getting all their nutrients and water from the air. The tree is just a place to grow.

Instead of immediately taking a left to head down Eastside Trail, we went fifty yards along Owyhigh Trail to see where Deer Creek tumbled under a bridge. The water was crystal clear, and the rocks had a grayish tone. Probably, all these rocks were granodiorite from the Ohanapecosh Formation. These rocks solidified in the early part of the Cascade formation, some 36-28 million years ago. Incredibly, they may have erupted at or even below sea level. According to geologists, this formation is close to 2 miles thick. My GPS unit said our elevation was 2,879 feet standing on this bridge. These mountains have been uplifted numerous times since then. Unfortunately, I should have taken the group another fifty yards along Owyhigh Trail. Just around the corner, Chinook Creek tumbled over a waterfall right next to the trail. I discovered this the following week when hiking that trail.

Back along Eastside Trail, the ferns and mosses were thick. Many of the mosses had dried out substantially, making their identification difficult. Dense mats of Rhytidiopsis species covered the ground and lay across some logs. The question was which species. At this elevation, it could be a pipe cleaner (robusta), but electrified cat's-tail (triquetrus) was another possibility. Stewart Hougen and Gary Brill's "Common Mosses – Lowland Westside PNW Forest" says that pipe cleaner can be the most common ground moss at this elevation. Dicranum mosses grew on many trunks, but their desiccated condition made them challenging to identify to species. The ferns, though, were outstanding.

Lady ferns were abundant along the trail. Their tapered compound leaves give a soft texture to the understory. Some had leaves spreading close to a yard in length. The smaller oak fern, though, really caught my attention. Its greenish-yellow leaves seem overly delicate, yet it stands with elegance. In several places, deer ferns lined the trail like columns along a walkway. Some had sent up their reproductive fronds in addition to their sterile fronds that are present all the time. The single leaflets on their fronds give them a distinctive appearance compared to those with compound leaves. Lynn Graf and Stewart Hougen found a wood fern that made me come back along the trail. This species initially resembled a lady fern, but its fronds aren't diamond-shape. The maidenhairs, with their circular stems and leaves emerging at an angle, always catch my eye for their beauty. They like wetter areas, places near waterfalls or under rock overhangs.

A dry creek came down from the west and spread across twenty or more feet of the trail. It looked like water had really rushed here earlier in the year, carrying boulders bigger than a softball, tossing and rolling them. Richard Burt picked up two softball-sized ones, and Stewart Hougen a third. Richard explained, "These rocks illustrate differences in composition of rocks that derive from magma that never reached the surface of the earth. The visible crystals in the first and third rock indicate slow cooling, at depth. The differences in coloration between the first and third rocks reflect differences in the chemical composition of the magma from which they derived. The darker rock was richer in iron and magnesium; the lighter rock would have more potassium feldspar and a higher silica content. The middle rock, with its variation in the size of the darker elements in it might represent metamorphosed breccia, a loose pile of diverse sized rock fragments."

They dropped these back in the stream bed. I had a hard time holding my excitement in wraps. This was fascinating information and so helpful in appreciating our hike.

Stewart immediately snatched up another. This one had large pieces of dark hornblende crystals in the gray texture. Hornblende develops when the magma has more magnesium and iron. Richard explained, "The black, needle-shaped minerals are, as noted, hornblende. According to an episode of Nick Zentner’s, hornblende is a good sign that the rock has undergone metamorphosis. While the rock appears similar to a granite or granodiorite, I think it reflects a different composition and history. As I understand it, the hornblende suggests that the rock has been deeply buried, experienced elevated temperatures and pressures, and has been altered from its original state. I’d guess that it’s a product of buried igneous rock from a volcanic episode that is older than the current Mt. Rainier."

Time moved along, and people needed a lunch break. The bridge over Chinook Creek was beautiful, but, in the sun, so I suggested we keep going another twenty minutes. Stafford Falls tumbled over a rock ledge and would provide a unique setting for a rest. The sounds came well before the falls were visible. A small side trail was difficult to spot, so I stood just beyond it, directing people to head down through the blueberries and huckleberries to find a good spot. Our group of ten had spread out along the trail, and I tried counting to make sure everyone had caught up. Lynn said she thought she was the last, but I hadn't counted ten. She went down to the group, calling back up to let me know that all were there. I probably forgot to count myself. Ha, always a challenge not to lose someone.

Chinook Creek tumbles over a 15-foot vertical cliff forming Stafford Falls, splashing into a large, round pool of crystal-clear water. The sides of the bowl are straight, maybe a hundred feet across, almost like a perfect circle drilled into the surrounding rock. The sound was loud, clear, and magnificent. Watching and listening to a cascade always sends soft waves through my body; it is like a magic spell.

"What made the falls right here?" I asked, looking at Richard and Steward.

"Probably, the rocks on this side were a little softer, more susceptible to erosion than the top. It would be slow, there has been a lot of time," Richard added.

My focus concentrated on the top part of the falls, then looked to the pool—no sign of any sediment. The water would slowly wear down the rocks, a fraction of a millimeter every year. It is a slow process, but it is what carved this valley over the eons of time. Although during the Pleistocene, a thousand feet or more of ice might be over our heads, and the pressure of all that ice would erode these rocks faster than just the water.

"Look at this," Lynn said. We had finished eating and were packing up to continue our hike.

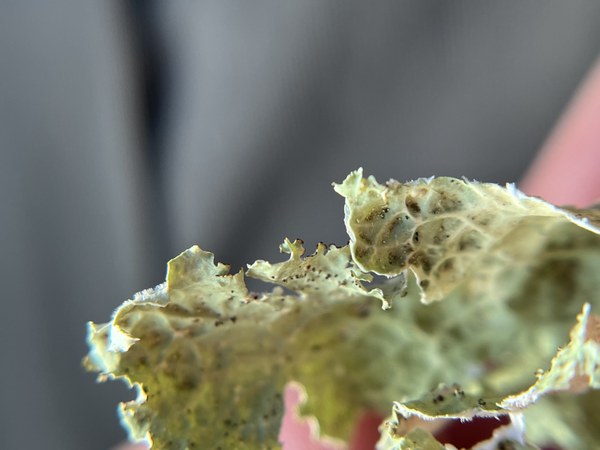

Lynn had poured some drinking water over two pieces of lichens she'd picked up from the base of a hemlock. The lichens on the trees were desiccated and lacked much detail. In the minutes we ate, the piece of Peltigera (Pelt Lichen) and Lobaria (Lung Lichen) had come back to life. They both had greened up. It was instant resurrection. Lichens have no vascular system and are dependent on water touching them. They can also go dormant for long periods and then come back to vibrant life with a bit of water.

"Check out the Lobaria, it has apothecia and no soredia, that makes it Lobaria oregana. This is a different species that we find around Seattle, which is Lobaria pulmonaria," Lynn explained, As she handed the oregana around, she added, "This is a good indicator that we are in old growth forest."

The flowers had mainly passed into their seed phase. Some, like thimbleberry, had fruit. These yummy little treats are the plant's way of encouraging an animal to disperse seeds away from the parent. Oval-leave huckleberries were tender bites for us to flavor along the trail, but it was unlikely we would be a suitable disperser for the plant. Some bunch berries had green fruit while others had turned red. Woodland pine drops and sugar stick were two saprophytic plants that lack chlorophyll and depend on others for their nutrients. The red ripe fruit of the elderberry made me stop several times. Once, I picked a bunch of these fruits in Western Pennsylvania, near my parents' farm, and made elderberry jam. To my chagrin, I can no longer remember how it tasted.

Stewart stopped me at one point, "Do you know the fruit of Queen's cup?"

“No,” I replied. It was a single purple fruit at the end of a spike emerging from the paired leaves. "That is what these trips are all about, learning from each other," I thought. The trick to leading these naturalist trips is creating an environment where everyone can share their knowledge.

The Ohanapecosh River came down from the west, feeding off the slopes of Ohanapecosh Park and south of Panhandle Gap. The waters tumbled and gurgled along, giving a great view. People needed a breather, and I thought this might be a good place, but everyone kept on walking. I'd been pushing us to make up some time after stopping so often to look at cool things. Someone had remembered that just a little farther, a large log in the shade would be the perfect place for a snack.

From the bridge, we looked down on a large rock outcrop and the top of the falls. "Look, there is a dike through those rocks," Richard said. To the left of the water was a massive piece of the Ohanapecosh Formation, probably granite or granodiorite. Running across it was some blackish rock, maybe a foot wide, and running the ten or twenty feet of the bigger boulder.

A crack in the Ohanapecosh rocks had allowed molten magma, sometime later, to push up through it, spreading the formation apart. "What kind of rock do you think that is?" I asked Richard.

"Hard to say without having a closer look, probably granite of some type," he replied. It was off-trail and no way to look more closely. I tried to imagine the pressure from below. Magma, under unfathomable pressure, was being pushed up against the continental crust. A weak spot, a weak line, breaks, and the liquid rock pushes up, separating and expanding the earth. Fifty million years ago, there were no Cascades in Washington. Two phases of building have happened: the West Cascades (40-17 million years ago) and the High Cascades (7 million years ago to present). My hands gripped the railing on the bridge as others continued along the trail. When did that magma ooze through that crack? This place was a glimpse of the processes that formed these magnificent mountains.

Around the corner was the correct place for a rest, snack, and drink. Several down trees gave us a chance to offload our packs, pull out the water bottles, and replenish our energy. Water tumbled under the bridge, jogged south, then fell almost twice the distance. All white with foam and action, perhaps a hundred-foot drop in total. Here was that carving again, happening at incredibly slow speeds, less than a fingernail thickness per century. I pulled a handful of pretzel nuggets from my pack, thinking, "How does one conceive of the change, the time, and all that has happened?"

It was 3 PM, and we had more miles to go than I'd hoped. From then on, I pushed us to keep up a reasonable pace, preferably faster than a mile an hour. The Douglas maples had started to turn color, and I thought that might be appropriate. My legs said I’d hiked enough well before the trail’s end. I'd said in the "Dear Hiker" letter that I'd hoped to reach the parking lot between 4 and 5 PM. We came in a quarter past five—seven miles in eight hours, about right for a "Naturalist's" hike.

What a beautiful trail!

Thomas Bancroft

Thomas Bancroft