Cowritten By Derek Stinson and Mike Schroeder

Washington is a haven for birders, and yet we still have huge gaps in our understanding of some of our most iconic wildlife. Take the White-tailed Ptarmigan for example. Many of you have likely spotted ptarmigan in the Cascades in their summer plumage, blending in with their rocky alpine habitat, but reports of these beautiful birds in their all-white winter plumage are few and far between. As a result, our knowledge of White-tailed Ptarmigan winter habitats in the Pacific Northwest are meager.

In fact, most of what we know about ptarmigan in winter comes from Colorado, where conditions are very different than in the Cascades, with smaller amounts of drier snow and colder temperatures. That’s why we’d like to invite you to learn more about the White-tailed Ptarmigan, so that you can help us spot and record these birds on your late fall, winter, and early spring trips to the alpine. In turn, you’ll help us scientists improve our understanding of their ecology, distribution, and needs.

The White-tailed Ptarmigan is the smallest species of grouse, and the only ptarmigan found in the lower 48. Ptarmigan are one of the few critters adapted to the rigors of alpine winters; their plumage changes color and they gain weight on a diet of willow and alder buds! When snow accumulations allow, they use their heavily feathered toes as natural snowshoes, and routinely roost under soft snow for protection from the harsh weather.

The female ptarmigan incubates 4-6 eggs in a nest on the ground while the male stands guard, sounding an alarm to identify an intruder. At hatching time, the male joins other males to summer at higher elevations, while the female leads the chicks away from the nest. As the young mature, adolescents aggregate and form flocks, while the adult males typically flock separately. Adults often return to the same territories and wintering areas year-to-year. The ptarmigan longevity record is about 15 years. If our local ptarmigan behave like those in Colorado, they shift to lower elevations with the first snowstorm, generally foraging on ridges where the wind keeps willow bushes exposed, or in drainages where shrubs are tall enough to be exposed above the snow. On windy days they may seek shelter behind rocks or in krummholz (stunted, windblown trees and shrubs near tree line), and during storms the flocks may move into stream bottoms and avalanche chutes.

White-tailed Ptarmigan in summer: male (left) and female (right). All photos by Kahn Tran.

White-tailed Ptarmigan in summer: male (left) and female (right). All photos by Kahn Tran.

As with all wildlife, human activities can negatively impact ptarmigan. One example is food made available to ravens, which prey on eggs and chicks. A second example is the impact we have on alpine vegetation. The greatest long-term threat to ptarmigan in Washington is climate change, which is likely to affect their alpine habitat and the connectivity between areas of occupation.

Report Ptarmigan Sightings this Winter

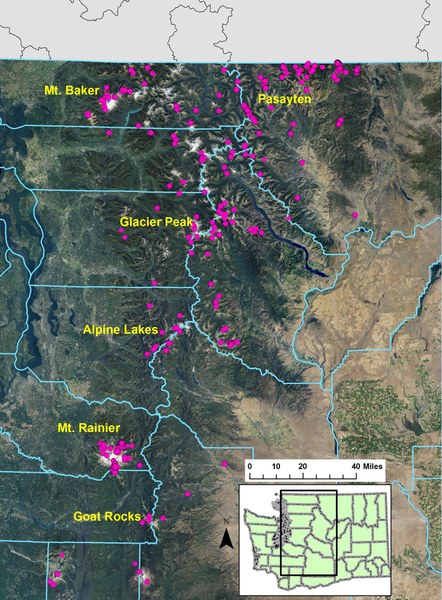

Our records of ptarmigan in Washington are nearly all summer observations. Help us change this by recording ptarmigan activity in other seasons, especially winter! Please:

- Take pictures! Pictures can tell us so much about behaviors and habitat.

- Provide detailed location information, including UTM or latitude-longitude, elevations, and a description of locations. Saying “near Paradise” isn’t as useful.

- Record any details about vegetation, weather, and behavior that you can.

- Be careful to distinguish ptarmigan (all white in winter; wings white year-round), from blue grouse (sooty or dusky; dark wings; larger birds), which are often found in subalpine conifers.

Observations can be recorded online at wdfw.wa.gov/get-involved/report-observations or sent to us directly at wildlife.data@dfw.wa.gov.

Derek Stinson is an Olympia Mountaineer and wildlife biologist. Mike Schroeder is a research scientist, who has specialized on grouse and is the current chair of the Grouse Group within the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. Both work for Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

This article originally appeared in our Winter 2020 issue of Mountaineer Magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, visit our magazine archive.

Derek Stinson

Derek Stinson