Trip Report

Intermediate Alpine Climb - Mount Rainier/Kautz Glacier

Two-day climb of the Kautz Route on Mt Rainier with an overnight at Camp Hazard, featuring straightforward ice pitches (AI2) and lots of penitentes. The descent was interrupted due to a medical emergency, leading to a helicopter rescue at 11,800' — huge thanks to the rangers and fellow climbers who helped along the way.

- Fri, Jun 27, 2025 — Sat, Jun 28, 2025

- Intermediate Alpine Climb - Mount Rainier/Kautz Glacier

- Mount Rainier/Kautz Glacier

- Climbing

- Successful

-

- Road suitable for all vehicles

-

Minimal open crevasses. Snow on the approach was firm and snow bridges were holding. Very straightforward approach across Wilson glacier (no parties were approaching via the Fan). Camp Hazard at 11,100' is mostly melted out with a few patches of snow providing running water during the daytime.

Trickles of silty water available on route between Camp Hazard and Wapowety cleaver from melting penitentes. Ice pitches were AI2 at most. A few good sticks but mostly rotten snow and frozen dirt. Good screw placements required cleaning off some of the rotten stuff first. Climbing length was about 2 full 60m pitches + a little simuling and then a long snow slog to the summit, crossing some cracks and passing over snow bridges. Once snow bridges melt, more zig zagging will be needed to end run crevasses. Penitentes all over the ice chute made for nice rest spots. 2 70m double rope rappels make it back down to the snow and walk over to the rock step and back to camp.

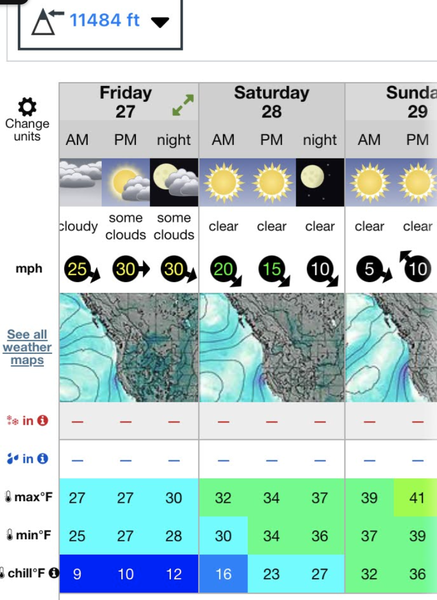

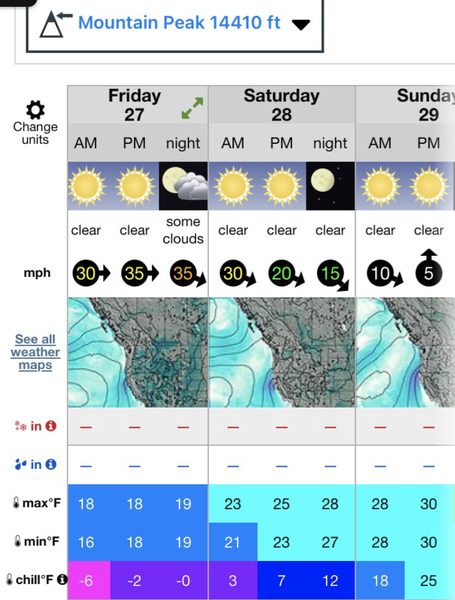

Weather leading up to our climb (Fri-Sat):

Stats

- 2 days/1 night

- 60m 8.5 Beal Opera

- 8 screws (used maybe 4), alpine draws, glacier gear

- Track - I used this track to plan our climb. The waypoints are very useful, and I added some of my own: Gaia link

Day 1: Approach to Camp Hazard

Jule and I picked up our reserved permits at 8am at the Paradise visitor center. There were already many parties in line, and groups without reservations were being turned away because all walk up permits for the popular routes - DC, Emmons - had been claimed already.

With our permit in hand we made our way to the Glacier Vista trail and crossed the Nisqually and Wilson glaciers. Some cracks are starting to snow but just barely. We were in a thick fog for most of the approach so we relied heavily on GPS for navigation.

As we approached the Turtle snowfield at ~9700' feet the clouds started to part and we could see glimpses of blue sky.

We decided to camp at 11,219' (46.8343472,-121.7629389), on an existing tent pad with a rock ring. The sites here are the last ones before descending the rock step. There are a few other rock rings around here as well as 20 feet below. The original site of Camp Hazard is higher up at around 11,400' ft. There are some flat spots here but it is in the line of rock and icefall and best avoided if there are sites lower down.

Day 2

Camp to summit

We departed our camp at 4:30am with a late start, hoping to have the first rays of light during the ice portion.

The rock step proved to be very straightforward as long as you don't make the same mistake we did and visit old Camp Hazard first. We realized quickly the rock step was just a minute from our camp so we descended back toward it and found the snow below was quite high, so the descending didn't require any rappels at this point in the season, even though there was cordalette slung around a large block with a rap ring.

After a rock step-n-scoot, we traversed over penitentes to the base of the first ice pitch.

The first ice pitch of mellow climbing with a few good screw placements just in case. At a grade of AI2 with pentitentes throughout, there are many spots to rest so the climbing is not very sustained. Still, 2 tools are highly recommended.

Above this pitch another section of walking up a snow slope to the second ice pitch.

We pitched out the second pitch the full 60m and simuled another 10m or until the slope lessened and it was more hiking than climbing.

Over the cleaver, the glacier has open crevasses with snow bridges still holding.

After a long while of slogging, we eventually arrived at the crater rim and Mazamas summit register where we took a break before descending.

Descent

At this point we were tired, but looking forward to a smooth descent and hopeful that we would feel more lively after descending to a lower elevation. Despite gravity working in our favor, the descent look about as long as the ascent due to the number of breaks we took.

As we descended down from Wapowety cleaver toward the top of the second ice pitch, Jule's breathing was becoming more labored, the opposite of what we were expecting given how descending was less strenuous than ascending, and that we were below 12,000' at this point. After careful consideration, we made the call to hit SOS on our InReach and notify emergency services of the situation. The group ahead of us graciously let us rappel off their double 70m ropes to the bottom of the second ice pitch, where we took a few more steps with the intent to continue to the next rappel and wait for assistance at camp. We reached 11,800' where Jule could not continue walking down so we sat down and continued messaging with emergency services. We had brought a sleeping pad, sleeping bag, and extra clothes with us so we hunkered down and waited.

After 2.5 hours a helicopter arrived with a long line and two climbing rangers who transported both of us and our gear to Camp Muir, where Jule was assessed by a medical professional.

I will spare the details as a more detailed write-up will be included in the incident report (now pasted in a comment at the bottom of this page.

Huge thank you to the Mount Rainier Climbing Rangers for their quick response during a recent climb that didn’t go as planned. The team handled everything fast, professionally, and with zero drama.

They got us out safely and made sure we were doing okay afterward, which honestly made a stressful situation a lot more manageable. It’s clear they know what they’re doing, and it gave us a lot of confidence in the middle of a rough spot.

Shoutout to the team of four who let us rappel off their ropes, offered to climb back up with supplies, suggested I join their rope team if the helicopter could only take Jule, and later packed up our gear at Camp Hazard and brought it down.

At the end of the day we all made it out safely. Jule is okay, and we were able to drive home the same night.

Isley Gao

Isley Gao