Back in 1906, it took newly-minted Mountaineers 21 days to reach the top of Mt. Adams (known by Native peoples as Pahto), horse-travel time included. Popular peaks like Chimney Rock and Eldorado Peak had yet to be summited by Mountaineers members, and so few Washington residents could access the Olympic Mountains that they might as well have been on the other side of the country. The mountains, and the species that lived within them, were mostly a mystery to Western eyes.

The first Mountaineer Annual states that the goal of The Mountaineers was not only to “tell the… ascents of our high peaks” but to share “the results of our scientific studies.” Early Mountaineers were just as excited by species as they were summits, eager to document the wildlife while pursuing ascents. They wanted to know how the view looked from the top and on the way up: which trees adorned the hillsides, what critters hid amongst the understory, and how glaciers could change the face of a mountain. The ecological curiosity embedded in early outings show that Mountaineers were not only alpinists, but naturalists at heart.

While early Mountaineers naturalist activities showcase an ecologically-oriented motivation for recreation, it was imbued with Eurocentric understandings of the natural world that failed to understand and recognize the history and culture of Native peoples inhabiting these lands. This historical backdrop will always be a part of our founding story, one that we continue to grapple with as we work to recognize and repair harm. Today, we look back on our early ecological endeavors with a critical eye and strive to recreate respectfully and responsibly while honoring the role Pacific Northwest Indian tribes have played - and still play - in stewarding these lands. With a more contemporary and critical perspective, we can look at early recreationists' ecological interests as an inspiration to re-instill mindful ecological appreciation into our backcountry experiences.

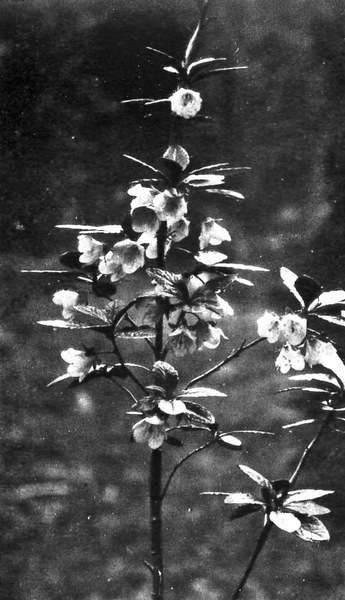

Heather from the 1912 annual. Photo by c.r. corey.

Summits for science

For early Mountaineers, trip beta was not only recreational, but ecological. Scattered in-between summit reports and outing recollections of early Mountaineer Annuals are ecological field notes describing the specimens and geological phenomena encountered during outdoor excursions. Examples include an essay on “The Seed Plants, Ferns, and Fern Allies of the Higher Regions of the Olympic Mountains,” which boasts a list of over 360 species and was considered the first study of its kind; an essay on “How to Know Trees,” which argues the importance of understanding a tree’s growth rate, soil preferences, and other life-habits; an essay on “The Whistling Marmot” and how the “flute-like cadence” of this “four-footed mountaineer” can easily be mistaken for a musician; and notes from the 1948 Juneau Ice Field Research Project, described as one of the “first major attempts to make any high level glacier studies in the North American continent.”

Annuals spanning from the 1930s to 1960s include notes on glacial recession and expansion in various peaks, a contribution to early conversations on glacial trends and climate impacts.

As frequenters of the backcountry, Mountaineers were in high favor at the University of Washington for their ability to access and collect natural materials of interest. During World War II, Mountaineers worked in collaboration with UW and the Red Cross to collect sphagnum moss — which had long been used by Native peoples to treat wounds for infection — to send to the military in France for use as surgical dressings. And a special note of thanks can be found in the 1912 annual from Professor O. B. Johnson for the gift of beetle samples. “Few of us ‘beetle enthusiasts’ have facilities for going to those places that your club is organized for,” he writes, “so I repeat it is fortunate to have such an ally.”

the cony or pika from the 1921 annual. Photo by william L. and Irene Finley.

Naturalists and conservation

The ecological musings included in Mountaineer Annuals were not only a means of documenting new discoveries but showcasing the biodiversity of the Pacific Northwest lands and waters to illustrate why these natural places deserved protection.

Over the years, our naturalist documentations gained significance as various parts of the state were under consideration for state and federal protection. During early conversations surrounding the creation of a Glacier Peak Wilderness Area, Mountaineers annuals bubbled with field notes demonstrating why the area was worthy of protection. A 1958 essay on the “Plant Life of the Area Surrounding Glacier Peak” describes the ecological and cultural significance of the area’s trees, arguing that “to see this great outdoor laboratory of natural science is to know immediately that it is well worthy of preservation.”

When the North Cascades was under consideration for National Park status, Mountaineers dedicated their 1964 summer outing to exploring and recounting the beauty of the region under the belief that “in view of the current efforts to make this area into a national park, as much of the area as possible should be seen by as many as possible.” The outing described flowers that were “rarely found as far south as British Columbia,” butterflies that had been “recorded only twice before in Washington,” as well as hummingbirds, goats, marmots, and bugs that beckoned federal protection.

Evolving naturalist methodology

As ecological knowledge advanced, so did our understanding of how to engage with the natural world with humility and respect. Early annuals note how Mountaineers could "easily handle female white-tailed Ptarmigans resting in their nests" or feed Gray Jays from outstretched hands. They also referenced attempts to enhance Washington’s natural environment by introducing invasive species so that Washington could resemble other alpine areas. The Edelweiss Committee was tasked with “securing seeds and plants of the Edelweiss from the Alps to further beautify the grand peaks of Washington,” and Alaskan plants “of surpassing beauty” were under particular consideration for introduction in our mountains. Although it’s hard to believe that city squirrels were once a prized symbol of beauty, Mountaineers were eager to help acquire these rodents to decorate urban parks, following examples from Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Virginia.

Now we understand the dangers of invasive species and feeding wildlife (“a fed animal is a dead animal”), reflected in the shifting of our teachings in recent decades. Today, we encourage members to enjoy the natural world with a perspective of humility and mindfulness, and to honor the places and wildlife Pacific Northwest Indian tribes have stewarded for thousands of years.

White rhododendron or snow brush, from the 1910 annual.

Naturalists today

While the reasons for exploring the backcountry have changed, the value of understanding its ecology remains. Lynn Graf and Stewart Hougen, co-chairs of Seattle’s Naturalist Committee, believe that ecology is still the “missing piece” in many outdoor trips. Their Intro to the Natural World course is an attempt to introduce folks to the biodiversity of the PNW and instill a love of the natural world among recreationists. The more recreationists know about the natural world, the more inclined they’ll be to appreciate and protect it.

“Our goals may not be that different from earlier times,” Lynn said. “We introduce those new to the PNW to the wonderful biodiversity here, from the intertidal zone to the alpine areas, and enrich the experience of more destination-oriented Mountaineers.”

This article originally appeared in our fall 2023 issue of Mountaineer magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, visit our magazine archive.

Skye Michel

Skye Michel