Asahel Curtis described Mount Shuksan in the first Mountaineers annual as “a beautiful mass of igneous rock with cascade glaciers flowing outward on all sides, except the north.” He, along with W. Montelius Price, claimed the first ascent of the peak in 1906 (Shuksan’s Curtis and Price glaciers serve as namesakes to the climbers). Asahel brought his faithful companion – a 10+ pound box-style camera – with him to the top. As was his trademark, he was simultaneously pioneering two fields: mountaineering and photography.

Aside from being the first party to summit the mountain, historians cite the climb as the ideological birthplace of The Mountaineers. Originally members of the Mazamas mountaineering club, Asahel and Price split off from the group’s Mount Baker summit attempt to climb Mount Shuksan together. “The outing lasted several weeks, so they had plenty of time to talk about forming a Seattle Club, the conversation apparently was wide ranging, and included five or six others,” Jim Kjelsden wrote in The Mountaineers: A History.

In the winter following the Shuksan climb, The Mountaineers was formed with the signatures of 151 charter members. 113 years later the club continues, sending at least a few groups each summer to the summit of Mount Shuksan in Asahel’s footsteps.

Destined for photography

Asahel Curtis, the youngest of four children, was born in Ohio in 1874. He spent his childhood in Minnesota, practicing photography with his older brother Edward, an apprentice for a local photography studio. The Curtis family moved to Washington in 1888, and Edward opened a studio of his own to support the family. Asahel went to work with him a few years later.

Edward gained fame through his photo series on Native Americans living throughout the U.S. Not to be outdone, Asahel’s photos from the Klondike Gold Rush popularized his work early in his career, and his nature and landscape photography would later be published nationwide.

Asahel’s techniques were markedly different than the processes of photographers today. With modern DSLR cameras and smartphones it’s easier than ever to capture everything we do, from the mundane to the extraordinary. And when using film, the development process is largely standardized.

A groundbreaker

As you can imagine, life was a bit different for Asahel and his 10+ pound camera box. The methods required to capture images in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were not streamlined, and individual photographers tinkered with the science behind the development of their photos to suit their own situation and style. They often tested a variety of techniques and materials to find the best fit. It’s fascinating to imagine the great photographs lost forever to the wrong mix of chemicals.

Color photography was still being developed and wouldn’t be available or take hold until after World War II. Handcoloring was one of the most popular ways to add color to the photographs. Black and white photos retained the detail captured by the camera, but the colors of the scene wouldn’t be lost. To give the images color, dyes or watercolor paints were added by hand. This process softened the photos, compared to today’s crystal-clear pictures. The images appear to occupy a space between painting and photograph, where the color is smooth and the images feel brushed, but they retain the detail and some of the contrast of a black and white photo. Much of Asahel’s work was hand-colored.

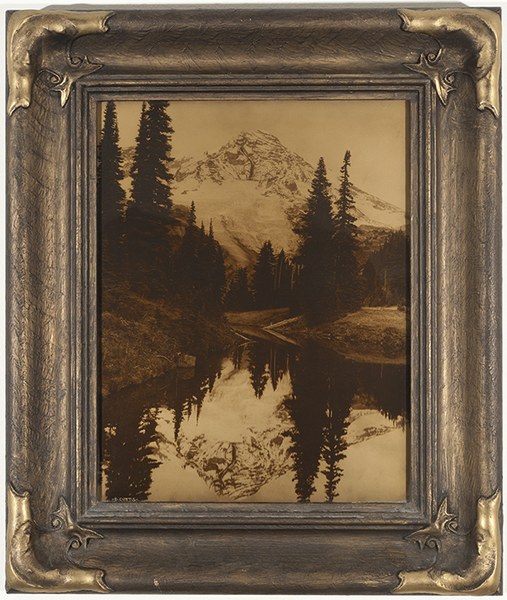

Asahel also produced orotones, a less popular printing style that required more work and skill to create. Orotones were so difficult that only a select few know how to create them today. To achieve this type of print, a photographer coated glass plates with a type of gelatin-emulsion, which was used to create a positive (think: an inverse of a film negative). After developing the positive, the back of the glass plate was covered in a mineral and oil mixture, often banana oil and gold leaf, giving the photos a very distinct gold-to-copper tone. The finished product retains the sheen of the mineral used, and the resulting image is striking. Asahel’s orotones, especially those containing mountain and lake reflections, offer stark contrasts and metallic highlights, and they remain the most remarkable of his work.

A framed orotone photograph of Mount Rainier and Mirror Lake. Photo by Asahel Curtis, Dan Davis Mountain Photograph Collection. Courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, Asahel Curtis, photographer, UW 39921.

A framed orotone photograph of Mount Rainier and Mirror Lake. Photo by Asahel Curtis, Dan Davis Mountain Photograph Collection. Courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, Asahel Curtis, photographer, UW 39921.

Paying it Forward

Outside of photography, Asahel contributed greatly to The Mountaineers. He used his strong mountaineering experience to organize The Mountaineers first outing to Mount Olympus, leading members on glaciers with the militaristic style of the time. “Each person was assigned to a company directed by a Captain, usually aided by a Lieutenant who brought up the rear and accounted for stragglers,” Kjelsden wrote. “Such Military order was considered essential from a logistics standpoint, and also because climbing teams on the summer outings did not rope up.”

Asahel aggressively supported tourism and access to Mount Rainier, and aided in the development and operations of the National Park. His organizational prowess complemented his leadership within The Mountaineers, and also resulted in roles on various planning committees in the greater Seattle area. His perspective did differ from The Mountaineers at times, as he was an ardent supporter of the construction of roads around Mount Rainier and opposed expansion of Olympic National Park.

Asahel’s legacy touches city development, photography, and recreation throughout the Pacific Northwest. He was integral in protecting and developing wild areas, and pushed along the conception and creation of The Mountaineers. He documented life in the northwest for decades and had a noteworthy and successful photography studio. Just like The Mountaineers, Asahel’s story is rooted deeply in the Pacific Northwest, and it’s hard to imagine the Pacific Northwest without him.

This article originally appeared in our Summer 2019 issue of Mountaineer Magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, click here.

Trevor Dickie

Trevor Dickie