After losing his best friend in a terrorist attack in Uganda, Tyler Dunning embarks on a journey to visit all 59 United States National Parks, to find nature, himself and eventually his broader outdoor community.

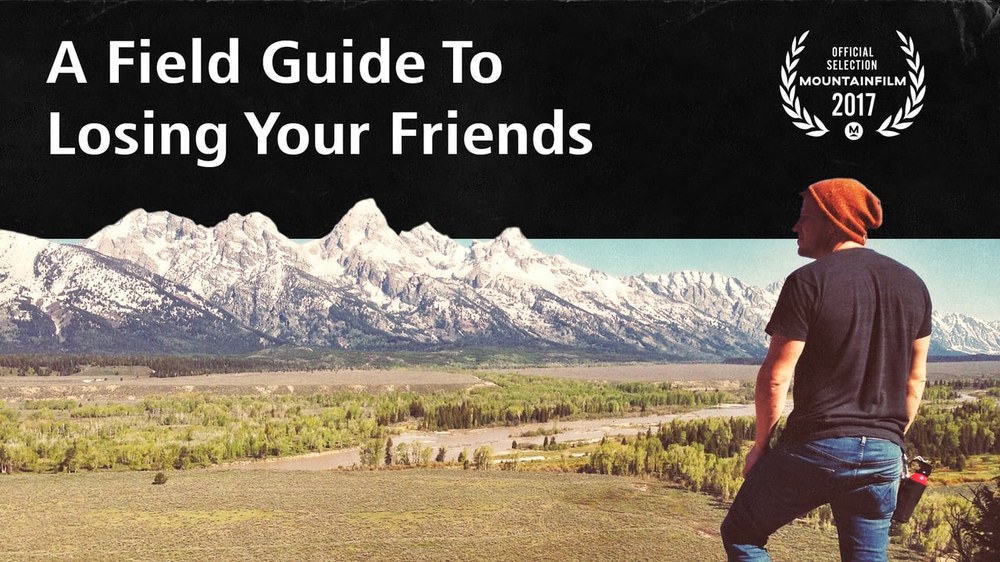

At this year's MountainFilm Festival, in collaboration with film director Chad Clendinen, Tyler documents his journey in A Field Guide to Losing Your Friends. We had a chance to speak with him briefly about his travels and experience. Tyler will also be available after the screening for an additional open audience Q&A.

Q: In your story, you start out describing nature as a place of solitude and healing. How did you make the transition from seeing the outdoors as a place of solitude to embracing more company on your adventure?

A: It was very organic. What's so cool about the parks was seeing how they unify people. A big indicator of that was when I moved back to California. We were all living in the same house with a bunch of people. There were sixty of us in one house. We started developing little cliques and microcosms. I started recognizing that I would invite people to a park and I would get a very disparate group of people that didn’t normally hang out together. I started seeing friendships forming and thought it was unique and powerful. I kept pursuing that and putting it out there. I made a promise to myself that I would always go on a national park trip by myself at least once a year. In Volcanoes National Park, I just went out there ten days by myself. I went to American Samoa for two weeks by myself. It proved to be difficult and became lonely and tiring. Especially Somoa, it's so humid, hot, I had bed bugs and I didn’t speak the native language. You grow so much in those experiences. I try to keep a good balance because I'm so introverted.

Q: How did you plan and choose which parks you visited?

A: It was all pragmatic essentially. When I initially started, I was living in Rocky Mountain National Park and visiting parks nearby like the Great Sand Dunes National Park. Then I was offered a job to move back to California in San Diego.

A big portion of accepting that job was recognizing and realizing that California had eight going on nine national parks. I also knew that I could fill my car with these other vagrants that I was living with and go see these places on the weekend. From there I started going to Joshua Tree, Channel Island, Death Valley, Saguaro, Sequoia, and Grand Canyon National Parks.

During that time, I was working for a non-profit being paid very minimally. It was a group effort of 20 to 25-year-olds wanting to see this natural world and seeing what California had to offer. Also, a part of the job position was going out on speaking positions or traveling around the country. There was one opportunity that came up when they needed one of their vans brought back from Washington D.C. They flew me out to Washington D.C. and I drove the van back while stopping atMammoth Cave, Hot Springs, and Shenandoah National Parks.

My family has become very interested in the pursuit. When people start recognizing me and seeing me do these things they want to jump on board. I always have people saying “oh when you go to Alaska I want to go on that one" or “when you go to the Florida Keys I want to go on that one". You just start accruing this network of places for sleeping and sharing the cost of gas with you.

Q: What's been your favorite National Park so far?

A: It's hard to pinpoint. The very thing that kept the goal alive was the fact that none of the parks were similar. You have so many diverse experiences, learning tools and ecosystems. If I could pinpoint it to one, it would be Kenai Fords up in Alaska. Just hiking up the Harding Icefields was the most amazing and intense hikes I've done. You're hiking through a temperate rainforest but then you also have these massive glaciers right next to you. Then you get up to the ice field and it's just this massive expanse of ice. You can also take boats and kayaks out in the water and see puffins and orcas and bald eagles. You see the glacier meeting the water's edge calving into the water. It's a beautiful, diverse and amazing experience.

Q: What did you read during your travels?

A: I did a lot of journaling but also reading. Those are byproducts of the activity. I didn't formulate my goals until 2010. I also wasn't a writer yet, I was doing just a little writing. I read a plethora of things but eventually made my way to an environmental bend. I read more Orion magazines, Edward Abby and Annie Dillard. Observational literary writers based in that natural vein. It is a difficult genre to work with and do well. I wouldn't say I'm an environmental writing or travel writer. I'd say I'm a mental illness writer.

Q: How has the experience on the book tour been? How has your relationship with your audience surprised you?

A: Yeah, I think that has been one of the waking things to what my writing is about because for a long time I wanted to be an environmental writer. With the release of this book, film and TEDx talks, I've had so many people come up. Strangers weeping holding me saying "I've struggled with mental illness" whether it's anxiety, depression, obesity, or suicide. I think it's something you can't openly talk about even though it's becoming more common within contemporary culture. Seeing someone speak about it so honestly and so curtly I think is rare for people. I've had teenagers come up to me and say "I've never been able to openly discuss my depression" and they would show me their suicide scars or them just saying "you've given me the courage to talk about my afflictions". That's happened across the board. It's been a little surprising but also refreshing.

The Mountaineers

The Mountaineers