by Dierdre Wolownick

In our suburban household in northern California, when the kids were little, we didn’t talk about conservation. But we did talk about love, care and respect — for our home, our selves, others — for our surroundings. When we went up to Lake Tahoe, we talked about how fragile an environment it was and how easily ruined. When we drove across the country to see grandparents, we talked about the landscape and the animals we saw, and how our behavior affects them. How many there are and how many there used to be.

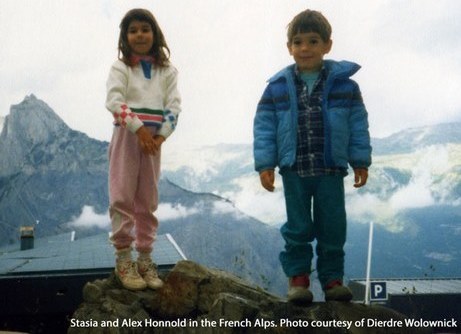

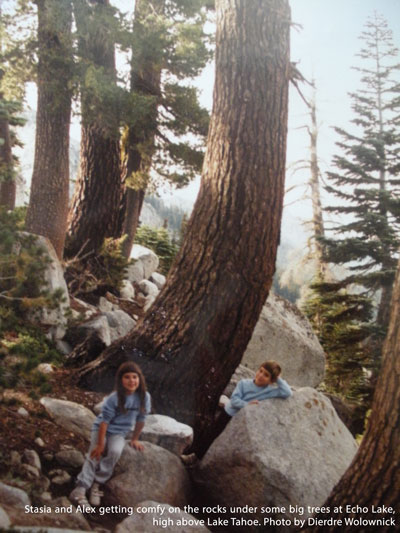

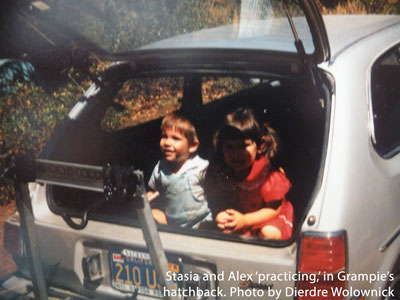

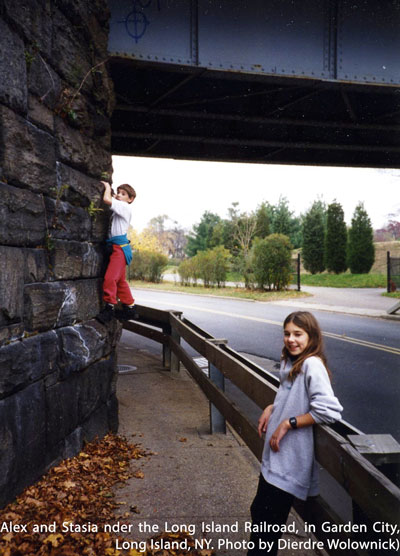

Young kids are expert travelers. In their new world, every day is an adventure; it doesn’t matter to them where that adventure takes place. So as soon as my husband and I had an appropriate vehicle, a hatch-back, we took the kids to the mountains, deserts, and national parks. We showed them where they lived and how beautiful it is. By the time Alex was five, they’d experienced the unique environment of Death Valley, walked reverently under the Sequoias, played at the beaches (and picked up litter). They’d been scared by bears running past us and awed by looking over into the abyss of the Grand Canyon. And at each place, they learned more about our world.

Dorothy Nolte, writer and counselor, had it right: Children learn what they live. The opposite is also true. If your kids have never walked among giant Sequoias, breathed their scented air and felt the religious-like silence of the forest around them, they probably won’t get too worked up if a lumber company decides to cut those trees down.

Decades after those years of outdoor experiences en famille, my son often talks about the value of close, personal interactions with nature. He lives ‘out there’ now, on mountains or crags, in deserts — wherever there are rocks to climb. In his keynote speech at the celebration of the 100th anniversary of our national parks in Washington D.C., he talked about the importance of having close-up, one-on-one encounters with nature. In many interviews, he cites our frequent family trips outdoors as the beginning of his love of the mountains.

But you don’t have to travel for your kids to grow up concerned about our world. Kids are sponges; learning is what they do, all day long. They observe, and they draw conclusions from their observations, the little scientists that they are. If they see that mom and dad value nature, that they don’t dirty it with litter, that they’re careful about what they throw out and think about where it goes, that they don’t waste water — all of those values are absorbed as kids observe and imitate.

The same holds true for aunts, uncles, friends and grandparents — everyone you frequent as a family. Do they share the same values as you, in terms of the planet we live on? If not, you might want to consider the effects of their attitudes on your kids. I don’t mean you should keep them away from them. On the contrary, seeing how other people behave and then talking about it with your kids can be a more effective lesson than if they’d never seen such behavior. A bad example can teach just as well as a good one. Keeping communication open is the key.

For the first two years of my daughter’s life (she’s two years older than her brother), she went everywhere on the back seat of my bicycle. We lived in Japan then and had no car (my husband and I both taught English as a Foreign Language). Biking was the only option or walking to the train station. Even though the station was over a mile from our house, as soon as she was able to walk, she would get to the station under her own steam, holding our hands, stopping often to explore, examine, and enjoy.

Nowadays, speed matters. A fast car is better than one that only goes the speed limit on the freeway. A high-speed train is better than a local bus that stops at every little town. And yet, I believe it was those first two very slow-paced years that influenced Stasia’s weltanschauungthe most. She turned out to be a thoughtful adult who chooses to live (in Portland) by bike only. No car. She composts at home, grows her own food, works toward stewardship at her job — she makes a million decisions every day in her life that connect her to the planet and help take good care of it.

When both kids started elementary school in Carmichael, California, the three of us biked there together every morning. No air pollution for us, no carbon-based fuels, no huge machines. We did the two miles ourselves, under our own power, and had great fun doing so.

A very simple thing my husband and I did as parents, that I believe influenced both of our kids as they got older and made their own life choices, was garden. My husband and I both loved growing things, so we grew a lot of our own food for many years. Both kids were encouraged to help with the planting, the care, and of course, the tasting. None of us will ever forget the anticipation of the sweet peaches and plums from Grammie’s garden and fresh tomatoes and luscious berries and other yummies from ours. Now, Alex is vegetarian and Stasia is vegan.

Even if you have a brown thumb, you can raise radishes, herbs, lettuce, potatoes, or zucchini. These are simple, easy-to-grow, foolproof crops. No vegetable or fruit from any supermarket can possibly match the taste of something freshly picked out of your garden. Your kids will know the difference. And that difference just might influence a decision or two that they make when they’re adults.

Examples are great, but kids learn mainly by doing. As parents, you need to decide what’s worth doing, what your kids will remember, and maybe learn from. Do yours spend more of their time outdoors, or reading, or making their own music — or in front of a tiny screen?

Mine were always active. When we went outdoors, to a national park or a state park or a local river, we hiked. While hiking, we learned things, all of us. Learning to see is a skill, and nature has a way of always providing us with fascinating, beautiful things to observe. Kids, being instinctive observers, excel at finding them. Nowadays, when we hike in the mountains or at a lake or wander the woods, Stasia knows the name of every plant we stop to look at, the tiny flowers we might have missed, the timid little bird that stopped to serenade us. She delights in sharing that knowledge, just as we delighted in getting her started on that exploration years ago.

At home, we would read to them. How could they avoid books? Both parents and three grandparents were teachers. Books were prized. We didn’t have a television set in the public rooms of the house (there was a small one in our bedroom), so when their friends came over, sitting and watching a screen was never a social activity. They played. They created. They baked, or read, or went outside and rode bikes or climbed trees, or just explored They, and their friends, never lacked for imaginative adventures.

That mindset continued throughout their childhood, and today, our favorite things to do together are outdoors. As we all get older, though, we’ve switched roles. Stasia got me psyched on running when I was 55. I’ve done four marathons and many half-marathons and smaller races — none of which would have happened without her example and the cheering of both kids.

When I drive up to Portland to visit her (from Sacramento, California), I always bring my bike. Last time, we pedaled several miles into downtown, and on the way back, we explored the brand-new bridge just built in Portland this year, Tilikum Crossing. Stasia was excited because it’s only for bikes and pedestrians. So of course, we had to ride across it. I knew they had a new bridge, but crossing it by bike was an adventure that opened new vistas of Portland, the river, and the joy of being outdoors with my daughter.

At 58, I started rock climbing, and I’ve had the greatest adventures of my life so far, sharing a rope with Alex in an alpine environment. In that relationship, he and I have definitely switched roles. When we go climbing, he’s in charge. He’s the pro, I’m the newbie. That alone is an adventure, after all those years of taking care of him.

When I moved from the east coast to southern California, in 1978, I got my first glimpse of Mount Whitney, the highest peak in the lower 48 states. At 14,505 feet, it’s one of the fifteen peaks in California that surpass 14,000 feet.

“Wow,” I remember thinking back then, “how exciting it would be to get to the top of that!” But I was a teacher and a writer and spent my life at a desk (when we weren’t camping or traveling). And then I had kids. I dreamed of Whitney all those decades.

In 2014, my son and his climbing partner, Cedar Wright, climbed all the fourteeners, free-solo (no rope, harness or protection). They traveled from one to the other by bike, calling this venture a “Sufferfest” (you can easily find videos about it online).

On the day they did Whitney, Stasia happened to be on a thousand-mile bike adventure ‘in the neighborhood.’ She joined them, and they summited together.

Last year, I had the opportunity to hike up (and up! and up!) and to stand on the very same spot at 14,505 feet, where both my kids had stood the previous year. What took my kids a few hours took me and my friends three days. But after thirty-eight years, I summited Whitney — one year after my own little adventurers had conquered it.

When the outdoors helps shape your life, you come to love it. It’s your own space, like your own room at home or your dorm room in college. Nature, the planet, becomes your partner in life, and like any partner, we want to help it be the best it can be.

That concept has no age limit. It’s a love story that any kid can understand.

Dierdre Wolownick is an author, retired language professor, and mother of two very talented and conservation-oriented kids, Stasia and Alex Honnold — both featured in 2015 issues of this magazine. Dierdre’s writing has been published world-wide. Her next book, for 2016-17, deals with the exciting challenges of raising a driven, extreme athlete. Her son Alex and his unique exploits in rock climbing have been featured internationally by National Geographic, “60 Minutes,” and others, and are well-known both inside and outside the climbing community.

Dierdre Wolownick

Dierdre Wolownick