by Mary Hsue, Mountaineers Development Director, with an excerpt from The Mountaineers: A History

In The Mountaineers: A History, longtime Mountaineers President Edmond Meany summed up the club’s mission in the 1910 annual: “This is a new country. It abounds in a fabulous wealth of scenic beauty. It is possible to so conserve parts of that wealth that it may be enjoyed by countless generations through the centuries to come… This club is vigilant for wise conservation and it is also anxious to blaze ways into the hills that anyone may follow.”

2016 marks the 110th anniversary of The Mountaineers and the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service. Since Meany’s time, generations of members have been inspired to do their part for wise conservation. This is a good thing for members today as we benefit from these Mountaineers who stayed true to the mission and cared to act and be a voice for our wild places. But even Meany could hardly have foreseen the numbers of people who now seek relaxation, and spiritual and physical renewal, in exploring this new country, where the “fabulous wealth of scenic beauty” now risks serious decline.

In the following excerpt and introduction to the main story of how Mountaineers secured long-term protection for Olympic National Park, I’d like members to appreciate the time, creativity, perseverance and passion of members before them, who did what they had to do for the protection of our wild places for outdoor lovers today. And I hope today’s members will be inspired to follow in their footsteps. For future generations.

Birth of a movement

By the time The Mountaineers was formed in 1906, an astonishing amount of the Pacific Northwest’s old growth forests had already been cut. Trees were logged just as fast as roads and sluiceways could be built, and loggers were headed ever deeper into the mountains.

By 1910, high-lead logging was in full swing and Washington had become the nation’s number one lumber-producing state. The timber, mining, and railroad industries heavily promoted such practices as the best use of land, arguing that wilderness areas were uninhabitable anyway, and so their only value was for the resources that could be extracted from them. The idea that an individual or business had any responsibility to future generations was unknown.

Unknown that is, except among a few groups, including The Mountaineers. Most of the founding members shared an intensity of purpose that nature’s gems must be preserved. The club’s first president, Henry Landes, issued the call for the conservation battles that would follow when he wrote in the 1907-08 annual that the organization hoped “to render a public service in the battle to preserve our natural scenery from wanton destruction.”

The Mountaineers laid out the club’s conservation objectives in its constitution: “To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation and otherwise the natural beauty of the Northwest coast of America.”

The club shared this philosophy with a growing national movement. Nature-loving Theodore Roosevelt, U.S. president at the time of the club’s founding, responded to the terrible waste of the nineteenth-century’s westward expansion by making conservation one of his top priorities. On the Pacific Coast, The Mountaineers along with the Sierra Club, and the Mazamas responded to this call and introduced the idea of wilderness preservation.

The Mountaineers at the intersection of conservation and recreation

Like the two other clubs, The Mountaineers tried to balance its stake in conservation with its desire for greater accessibility to the mountains. This paradox was recognized from the start. While Landes wanted the club to oppose wanton destruction, he also sought to make wilderness areas “accessible to the largest number of mountain lovers.”

All three clubs working together succeeded in promoting the recreational opportunities and the scenic value of the mountains, would prove to be a lasting contribution. Together the clubs’ annual outings drew thousands of people into the wilderness, and the publicity that resulted did a great deal to sway public perception in favor of recreation and away from commercial exploitation. The outings allowed the budding conservation movement to gain wider acceptance and set the stage for the titanic battles over resources that would follow.

Long-term protection on Olympic National Park

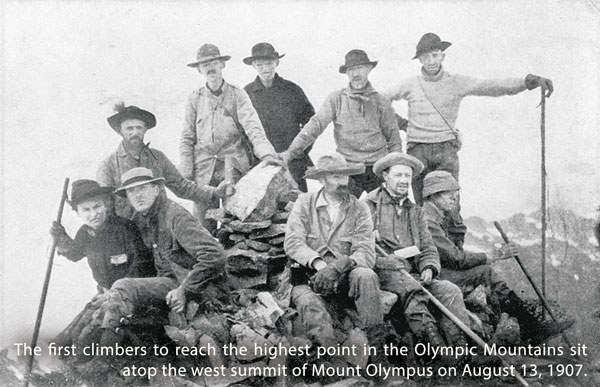

One of the earliest and longest-lasting of the club’s environmental battles was over creation of a national park in the Olympics, which The Mountaineers ironically helped open with its first summer outing. The subsequent publicity alerted industrial concerns to the relative ease of access, which before that time had been considered extremely difficult.

In the years that followed until 1938 when Olympic National Park was established, conservationists battled mining, timber, and railroad interests that sought congressional action to abolish the entire dedicated area which had been designated an Olympic monument area and only half the size originally imagined in 1910. Mountaineers members kept up the cause, and in 1938, when Olympic National Park was finally established, it included an increase in size almost equal to what had been lost in 1909.

The Mountaineers later got back in action and played a pivotal role in securing the long-term protection of Olympic National Park. Unknown to the public, the National Park Service had opposed creation of the park at the same time that FDR and Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes had been pressing for it. In 1952, the Park Service director authorized the park superintendent to undertake “salvage” logging within its boundaries. The result was the stripping in the mid-1950’s of more than 100 million board feet of lumber from the park.

Power of Mountaineers' voices

The Mountaineers did not discover what was happening until Paul Shepard, executive secretary of the Garden Clubs of America, became head seasonal ranger at the park in the summer of 1956 and witnessed the damage being done. Shepard overcame the reluctance of other seasonal rangers to say anything. Two of them, Mountaineers members Bill Brockman and Carsten Lien, went to the club’s conservation committee for assistance. A joint committee representing several environmental organizations was created, and included Polly Dyer, conservation committee chairwoman; Chester Powell, Mountaineers president; Patrick Goldsworthy, representing the Sierra club; Emily Haig, representing the Audubon Society; John Osseward, representing Olympic Park Associates; and Philip Zalesky, vice-president of the Federation of Western Outdoor Clubs. All were members of The Mountaineers.

The night their report was presented to the conservation committee, all the members agreed to send the following telegram to the director of the National Park Service: “request immediate cessation of logging operations in Olympic National Park pending confidential investigation of possible irregularities into logging park timber.”

Without saying it outright, the telegram suggested a suspicion of graft. It was a political bombshell and got immediate results because the 1956 presidential campaign was in full swing. The National Park Service director met with the joint committee, and when pressed on the issue declared, “The National Park Service has taken a calculated risk. There will be no further logging in Olympic National Park.”

Be the voice for future generations

For over a century, The Mountaineers has stayed true to its roots and continues to be a leading voice for important issues at that intersection of conservation and recreation. And it’s just as important as ever to get involved. The recent expiration of the Land and Water Conservation Fund for the first time in 50 years shows a shift in national priorities. Those of us who care about conserving our lands need to exercise our rights as citizens and speak up — just as generations of Mountaineers have done before us. I hope you are inspired to join in the fight so that future generations can enjoy the places we love to play.

To find out what conservation projects The Mountaineers is currently focusing on and to learn how to get involved, go to mountaineers.org and click on the "Conserve" tab.

Mary Hsue

Mary Hsue