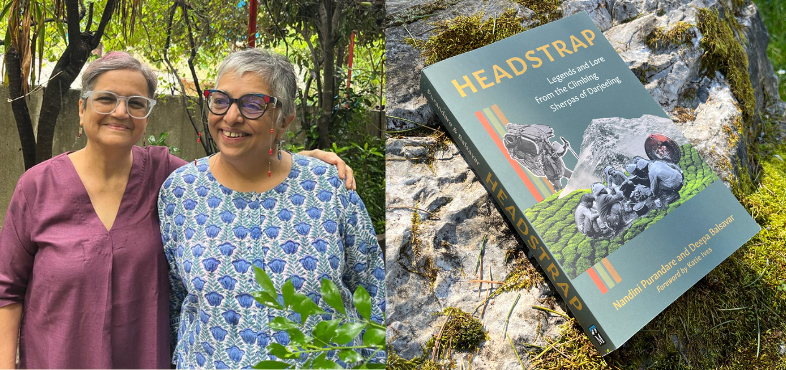

Headstrap authors Nandini Purandare and Deepa Balsavar share insight into the start of this decade-long project.

Excerpted from Headstrap: Legends and Lore from the Climbing Sherpas of Darjeeling

The seeds of this project were planted in early 2012 in a remote area of Arunachal Pradesh in the eastern Himalaya. We were hiking with our old friend and trekking companion Harish Kapadia, modern India’s preeminent explorer. Travels with Harish are always filled with songs, stories, and anecdotes about the people he has met while traveling. He told us a fascinating story about the legendary climber Pasang Dawa Lama of Darjeeling— jumping naked into the icy waters of a Nepali river to advertise his having slept with one hundred women—that ignited our imagination about the community of Sherpa climbers in that hill town. We wanted to know more, and that’s how it all began.

At the end of our first visit to Darjeeling, in April 2012, we made a promise that this book seeks to fulfill: to record and share Sherpa stories and histories from this region. We uncovered many tales over the coming years, in the narrow, often grotty lanes of Toong Soong, a Sherpa settlement in Darjeeling. We found them in the warm homes of the sons and daughters of Sherpa heroes from decades ago. We traced connections and attempted to chart family trees. We discovered that there are new Sherpa climbers in Darjeeling today, but they are separated geographically, historically, and technologically from those who came almost a century ago. We dug into forgotten papers and books published by The Himalayan Club, set up in India in 1928 to encourage climbing and exploration in the Himalaya, and met with climbers all over the world who shared their memories with us.

Many of the Sherpas and other people we wanted to meet had died without anyone hearing about their remarkable lives. Over the years we returned to Darjeeling for months at a time to learn about these men and women. We kept at it, gaining confidence, making friends, and listening. The experience was both humbling and uplifting.

During the hours we spent in different homes, we realized and learned many things. We realized that memory is fallible. More importantly, our memories are not linear; they emerge from emotion, not logic, and not necessarily from fact. We occasionally came across discrepancies, either between how two people recalled the same event or between an oral recounting and a written one. For example, we interviewed Kusang Sherpa in 2013 about his arrival in Darjeeling and entry into climbing, but in his autobiography published a few years later, he recounts different details. In such cases, we have done our best to determine and recount those versions most likely to be accurate.

It took time to understand that it was the memories, personal and intimate, rather than the written accounts, that should be the focus of our work—after all, memories let us into people’s hearts and minds. Still, stories from memory are often left with gaps, which we worried about how to fill. It took time to understand that we could string together a narrative despite these imperfections, even as some facts have likely been lost along the way. We had to learn not to ask our interviewees questions that reflected our modern intellectual concerns and may be insensitive to our subjects’ conditions and priorities at the time, like “Did you ever think of doing something else to earn your living?” or “What did the women feel when their men left for the mountains?” Most of all, we learned that many Sherpas who appear in expedition accounts, both written and oral, were legendary climbers, but had no family or heirs to their stories left in Darjeeling. We are sincerely sorry that we could not cover them.

We recorded hundreds of hours of conversations, which had to be painstakingly transcribed. Narrators spoke in Nepali, Hindi, and English. The interviews were filled with hesitation, self-contradiction, doubt, and gossip. A single hour of recording took many hours to simultaneously translate and transcribe. It took a few years to record and subsequently transcribe all those conversations and interviews.

Interspersed with our trips to Darjeeling were our home lives in Mumbai, our day jobs, and our family obligations. We also took trips to other cities and towns to meet other people who knew these Sherpas and to visit libraries for research. In the early years, we were also constantly writing grant proposals and meeting with potential donors to the project. A travel agency, Cox & Kings, bought our airplane tickets for a few years, but we worked on a shoestring budget for everything else.

The hardest part came later when we had to sift through accounts, facts, dates, and names, and verify and organize them. Over 150 interviews, representing hundreds of hours, had to be condensed into a cohesive, readable, interesting narrative. Much had to be left out, in order to let the diamonds emerge.

Over the years, place names have changed. For instance, Bombay became Mumbai in 1995, and Calcutta became Kolkata in 2001. For consistency, we have gone with the more modern, Indian names for each place regardless of the timeline of the events being described, unless the reference appears in a direct quote.

A decade is a long time to write a book. Many of our narrators have died over this period. Still, we hope to keep their memories alive on the pages of this book—not an anthropological work or an academic tome but a tale about a fascinating community of mountain people and climbers. Finally, we take full responsibility for any oversights, factual inaccuracies, or misinterpretations.

A Note on Headstraps

All across Darjeeling and Nepal, porters can be seen carrying heavy loads secured by straps across the head. Officially called tumplines, these are known locally as headstraps, or namlo. During Himalayan climbing’s early decades, all loads were carried using the headstrap. Even today, porters carry loads up to basecamp this way.

There is no single origin story for the headstrap. Traditionally, it could be a strip of leather, fabric, or rope that was knotted, looped, or buckled around a load and worn across the top of the head. Although this technique is found in almost every culture, Sherpas are probably the most famous headstrap users today, using it to carry loads as heavy as their own body weight. Even when offered modern packs, they often prefer their cane baskets, called doko, secured with the simple strap.

Headstraps are known to be ergonomically efficient and physically healthy. They enable weight to be distributed evenly down the back and allow for lung expansion without restriction, unlike backpacks, which often restrict the chest. However, using them safely and comfortably requires years of training and spine strengthening.

Headstrap: Legends and Lore from the Climbing Sherpas of Darjeeling is now available. Find it here.

Mountaineers Books

Mountaineers Books