One of my earliest crack climbing memories is of a notorious route on Peak District gritstone called The Vice—a short, steep hand-and-fist crack that requires a bit of brute force and tenacity, but with the correct techniques is not overly difficult. A confident twelve-year-old me spotted the HVS (5.10) grade in the Stanage guidebook, thought “that’s within my ability,” and then spent the next 20 minutes dangling on the end of a tight rope with my feet paddling the air and brushing the ground.

I managed only a single move.

It’s not uncommon to have a heartbreaking experience when you start crack climbing as the techniques required are so far removed from anything you might have previously learnt in climbing. But stick with it. Since my own demoralizing efforts on The Vice, I have gone on to repeat or establish many of the world’s hardest crack climbs. Miles of outdoor crack experience and indoor wooden crack training, along with many hours of crack climbing coaching, have given me the experience and the confidence to write Crack Climbing: The Definitive Guide.

My goal from the start was to provide a single point of reference for crack climbing technique. The aim is to show you the different techniques and give you an understanding of why and how you use them. Then you can put them into practice with confidence and your climbing will improve.

The Five Rules of Crack Climbing

There are five basic rules to abide by when it comes to climbing cracks. If you follow these rules and apply them to all aspects of your jamming techniques then you will experience less pain and a higher level of enjoyment and success.

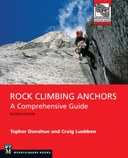

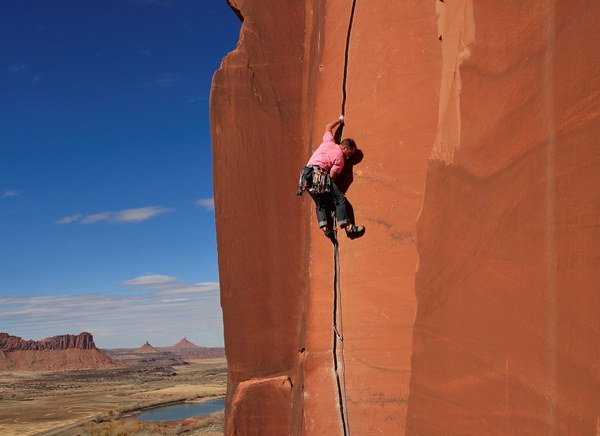

Martin Kocsis climbing the immaculate thin hands and finger crack of Scarface (5.11a) on the Wingate Sandstone at Indian Creek, Utah. Photo by Mike Hutton.

Martin Kocsis climbing the immaculate thin hands and finger crack of Scarface (5.11a) on the Wingate Sandstone at Indian Creek, Utah. Photo by Mike Hutton.

Rule 1: Fill the space efficiently

Crack climbing is climbing the spaces between and inside the rock. So, with all jams, you should try to fill those spaces as efficiently as possible. You therefore want to insert as much of the body part you are jamming with inside the crack before you even start doing any of the techniques needed to execute the jam itself.

Many people start performing the dynamics of the jam before the body part is fully in the crack. This means they get less surface area of jam touching the rock—and therefore a poorer jam. Why use only two fingers on a large crimp when you could use all four? It’s the same with jamming: why insert only half of your hand when the crack can gobble your hand to wrist depth? Get that body part right in there.

Rule 2: Use your body as a jamming device

When the part of your body that you want to jam with is inside the crack, you have to expand it to fill the space and make it stick. There are lots of different ways that this jamming and expansion can be achieved.

Let’s imagine your body is a rack of gear, with lots of different shaped and sized pieces. What you do with your body when you are crack climbing is the same as what you do with your climbing gear: insert it into cracks.

A rack of gear has lots of pieces of different sizes, from the smallest micronuts through to the biggest cams and Big Bros. Likewise, your body has lots of different size options available to insert into the crack, from the diameter of your little finger right through to the length of your whole body.

Your gear has lots of options for ways it can expand and twist to make sure it sticks in the rock. Your body also has lots of twisting and expanding mechanisms thanks to the movement in your joints.

Your gear generally needs two or more points of opposing pressure to stay in place. Your jam also needs two or more points of opposing pressure on the crack walls to make it stick. (It’s important to remember that a jam will only work when body parts are touching both sides of a crack feature.)

There are two ways that your body can jam: passive and active.

- Passive (like placing a nut): the jam is created by constrictions in the rock which allow a body part to be slotted in and wedged, enabling your jam to stick. The jam works because the constriction becomes too small for the body part to pass through. This type of jam requires minimal strength so you should try to use this type of jam as a first option.

- Active (like placing a camming device): the jam is created by a range of movement from you—either by twisting, rotating, or expanding. A downwards force (your weight pulling on the jam) along with this movement of the jam creates outwards pressure and friction on the crack walls enabling your jam to stick. A downwards force (or pull) is hugely important in making the jam stick.

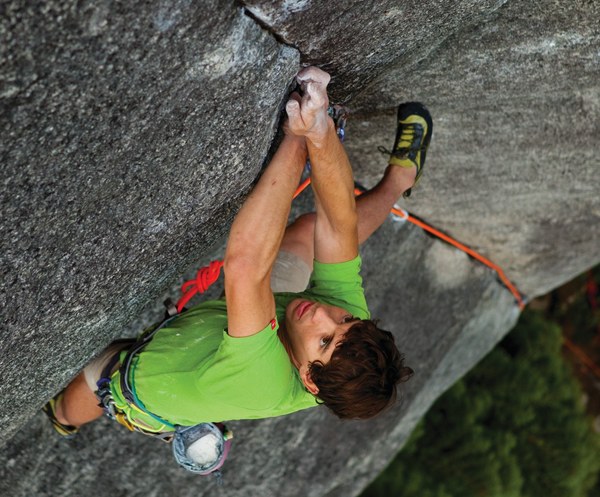

Alex Honnold on Leviticus (5.12d) at Murrin Park in Squamish. Photo by Andrew Burr.

Alex Honnold on Leviticus (5.12d) at Murrin Park in Squamish. Photo by Andrew Burr.

Rule 3: Keep everything in line with the crack

All body parts should be twisted and orientated in such a way that makes their final position—before you move up on them—parallel and in line with the crack. Let’s try to understand this concept better:

Imagine that climbing a crack is like climbing a ladder. Easy! The legs of the ladder represent the edges of the crack and each ladder rung is a jam. Now imagine you’re climbing the ladder and your limbs and body are parallel with the ladder’s legs. Your elbows will be pointing downwards as this generates the best force for pulling yourself up with your arms. Your knees are pointing upwards as this generates the best force for pushing yourself up with your legs. If your elbows and knees start twisting out to the side, then this will affect their ability to pull up and push down on the ladder’s rungs. It will start to feel like you are pulling and pushing outwards to the side—and climbing efficiency will be lost. Exactly the same principles apply when climbing a crack: elbows should be down and knees should be up. When everything is in line with the crack, effective jamming is in action. If your body parts aren’t in line, you will not be able to pull up and push down as effectively. Climbing a crack is like climbing a ladder.

Rule 4: Use structure not strength

With all crack climbing, you use the frame (structure) of your body to stay in and on the rock. Joints, ligaments, and bones: you are aiming to lock these into the crack in such a way that you can hang off them using minimal or no muscle/tendon contraction.

Imagine a body with no soft tissue, just a skeleton with ligaments holding the bones together. If you twisted, rotated, and expanded the skeleton’s bones you would be able to create shapes which could fit and lock into cracks without any “holding power” from the absent muscles and tendons. This is what you are trying to achieve when using your body in a crack.

You are locking your body into the rock. Not holding your body on to the rock.

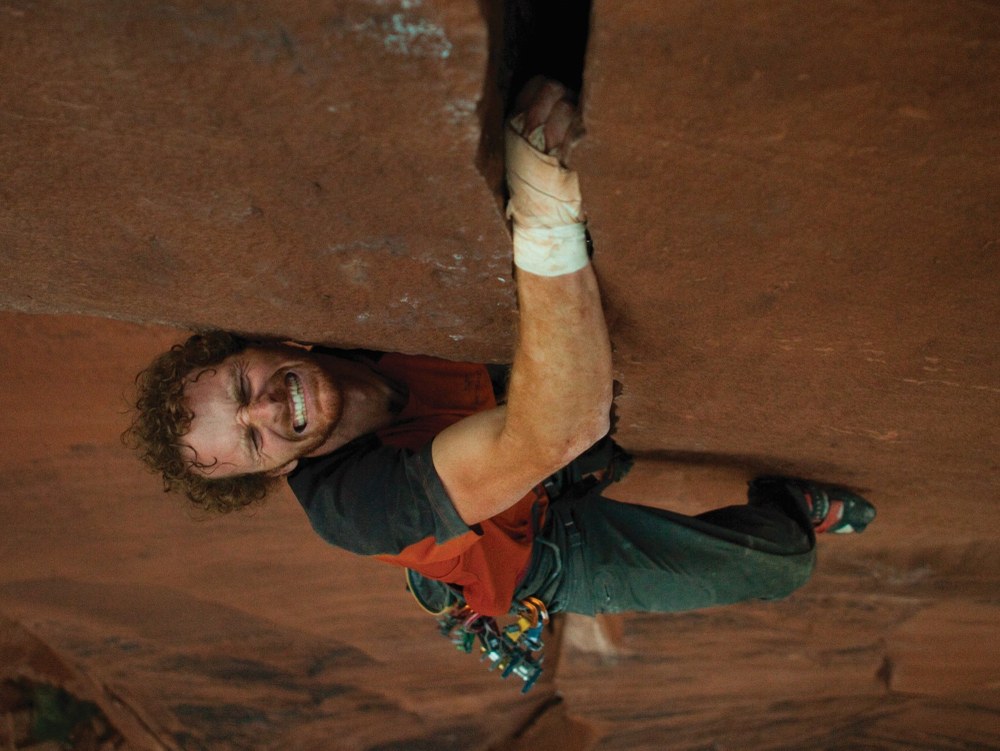

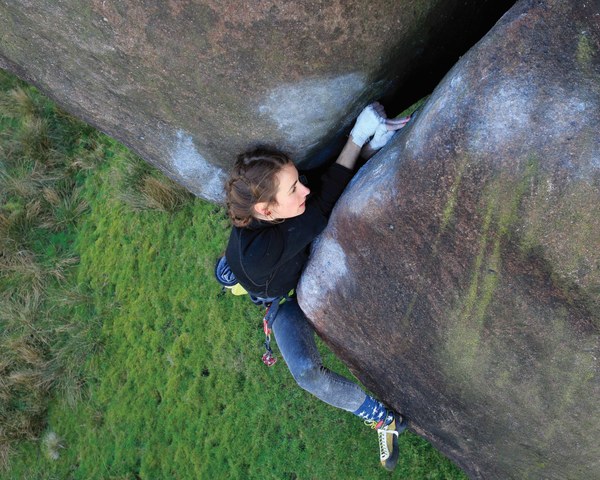

Mari Augusta Salvesen during the first female ascent of classic gritstone offwidth Ray's Roof (5.12d) at Baldstones in the Peak District. Photo by Mike Hutton.

Mari Augusta Salvesen during the first female ascent of classic gritstone offwidth Ray's Roof (5.12d) at Baldstones in the Peak District. Photo by Mike Hutton.

Rule 5: More surface area between skin and rock equals a better jam

The more contact that your jam has with the rock, the better it will feel. By orientating your jam correctly to the rock’s profile, you will get more surface area of the jam touching the rock and therefore a more solid jam. Let’s try and understand this concept better:

Your climbing partner has made you a jam sandwich. Between the two slices of bread is a layer of strawberry jam. They pass you the sandwich, but when you bite into it you find they haven’t spread the jam right to the edge of the slice, so all you get is a mouthful of bread. You find they have only spread the strawberry jam in the center of the sandwich and there is barely any surface area of strawberry jam touching the bread. Very disappointing. You ask if the jam can be spread right to the edges of the bread to cover the whole area. You try the sandwich again; this time you get a mouthful of strawberry jam and the jam sandwich tastes great!

Let’s take this strawberry jam sandwich example and apply it to crack climbing. The slices of bread represent the crack walls and the strawberry jam represents our body jam. When you put your jam in between the crack walls, if there is minimal surface area contact between skin and rock when you engage the jam, then just like your strawberry jam sandwich, the end product will be disappointing. However, if you create lots of surface area contact with your jam and the crack walls, then just like your fully spread strawberry jam sandwich, the taste—of success—will be sweet.

More surface area between skin and rock equals a better jam.

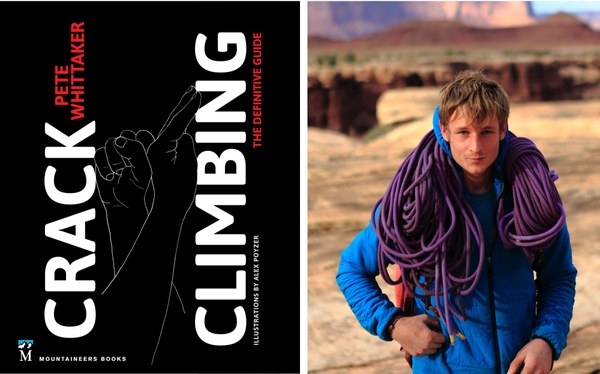

Excerpted and adapted from Crack Climbing: The Definitive Guide by Pete Whittaker.

Photo at top: Rob Pizem fist jamming on Willow (5.11+) at Willow Buttress in Labyrinth Canyon, Green River Canyon, Utah. Photo by Andrew Burr.

About the book

If you want to climb well, you must master the art and science of crack climbing. Luckily, elite British climber Pete Whittaker has written just the book you need. Drawing on his years of experience, Whittaker teaches you how to develop and use scores of techniques, and he explains when and why they'll work. Organized by width of crack (finger, hand and fist, offwidth, and chimney), Crack Climbing covers everything from basics like the hand jam through advanced techniques including the sidewinder and trout tickler. To keep you motivated, Whittaker includes interviews with some of the world's top climbers. Learn from the best, including not only Whittaker, but also Beth Rodden, Lynn Hill, Alex Honnold, and more.

Pete Whittaker

Pete Whittaker